USHS Blog

Sightings. Mediterranean Surveillance and its Imperial Precedents

Few of us vacationers who currently descend on Mediterranean beaches may notice it, but the sea is always under steady vigilance. When we unroll our beach towels and pitch our parasols, we are actually at the outer fringes of a vast zone of intense surveillance. Warships, helicopters and satellites crisscross as they scan gridded sections of the waving realms. Such surveillance work, a recent report from the Forensic Oceanography group once again indicated, is used in illegal pushbacks of migrants that try to cross the sea, at times leading to their deaths. Contemporary as these questionable efforts are, they are not entirely without precedent. Figuring out who is crossing the sea, in what direction, and with which intentions was also a primary concern in the early nineteenth century, in an age of imperial expansion. Over the last few blogs, we have seen how nineteenth-century security practices begot the beginnings of modern tourism, but there is a flipside to that story too. A flipside, that is, of overseeing and checking movement. A mixture of agendas and interests, both official and private, were at play then, as they still are now. After all, surveillance is not just about looking; it also entails acting. To see just how far its consequences may reach, we need only turn to 1827, to the port of Marseille on the eve of the French conquest of Algeria.

The opening of Marseille’s Palais de la Bourse, the current seat of the Chamber of Commerce. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Overseeing the state and the non-state

Anyone who has been fortunate enough to cross borders by flicking a passport or uploading data into a visa waiver program, has experienced the current preeminence of the state in matters of surveillance. In the early nineteenth century, however, such official preeminence was much less clear-cut. Divisions between state and non-state were blurry as sets of information flowed freely between different interest groups. This was a time in which trade companies still carried out duties that we now consider squarely under the state’s control, such as appointing and instructing diplomatic representatives. The conduct of surveillance neatly reflected this context.

Organized merchants themselves kept track of what was happening out at sea. In France, that role was for a significant part fulfilled by the Chamber of Commerce in Marseille. On the other side of the sea, the authorities of the Regency of Algiers likewise drew intelligence from the outstretched commercial networks of the most important trading houses, which were manned by Jewish families of Livornian origin. Though it may seem like it, this was no nineteenth-century version of outsourcing surveillance work. Family members of the Jewish houses in Algiers often held other official or advisory functions, while the board members of the Chamber of Commerce in Marseille were directly involved in the functioning of the French consular service throughout the Mediterranean. Still, the ways in which these agents amassed, processed and utilized their knowledge did allow them to push their private agendas of securing overseas markets at low shipping costs.

The launch of a ship near Marseille, by François Barry (c. 1869). Source: Wikimedia Commons

Corsairs and convoys

That those agendas could intertwine with imperial expansion is shown by the case of Marseille. War had broken out between France and Algiers in June 1827 and the merchants of that city faced the consequences. For the first time in decades, they saw their cargoes and vessels targeted by Algerine corsairs. The government in Paris initially did little, adopting a blockading strategy that was mainly intended to buy time. The blockade of Algiers and its adjacent ports was hardly effective, and soon reports came flying into Marseille of captured goods and of captains who dared not go to sea. One example involved a group of vessels carrying olive oil and linen that was stuck in Tunis, for fear of meeting corsairs. The traders who saw their cargoes confiscated or their shipments delayed turned to the Chamber in great numbers, detailing the extents of their losses. Within in the first months of war, the board members of the Chamber already had stores of information in their hands.

That data was kneaded into relevant, usable forms. Whenever a captain in the docks reported on a sighted corsair, the Chamber put the information in a standardized form and posted (or telegraphed) it to the maritime prefect in Toulon – the main base of the French Mediterranean fleet. Claims for indemnities were forwarded to the government in Paris, while complaints over losses and rising insurance rates were grouped together and turned into petitions. The Chamber in Marseille also used the information to bring about convoys – one of which liberated the ships anchored at Tunis from their cautious custody. Yet, these convoys were an obstruction as much as a solution. Letters of complaint from merchant captains and navy commanders arrived on the desks of the Chamber as well. Convoys were too infrequent, while pilots did not listen to commands, sometimes leading to their immediate capture by a nearby corsair.

The fruits and frustrations of surveillance

As discontents mounted, the fruits of surveillance began to be used for more explicitly political ends. Security at sea seemed to be faltering. Therefore, calls for more assertive policies could increasingly be heard. The first French parliamentarians who argued for decisive measures against Algiers were not coincidentally deputies from Marseille. One of them, Pierre-Honoré de Roux, denounced France’s ‘passive war’ in May 1828. He referenced the cases of merchants who fell into corsair hands to argue that a blockade was insufficient. Instead, he proposed to end the conflict through a military expedition. Subsequently, France could create fortified points on the North African coast and ‘peacefully’ open up the region to further commercial exchange. The intelligence of surveillance was thus inserted in a political proposal that, when eventually executed, had far-reaching and not at all peaceable consequences.

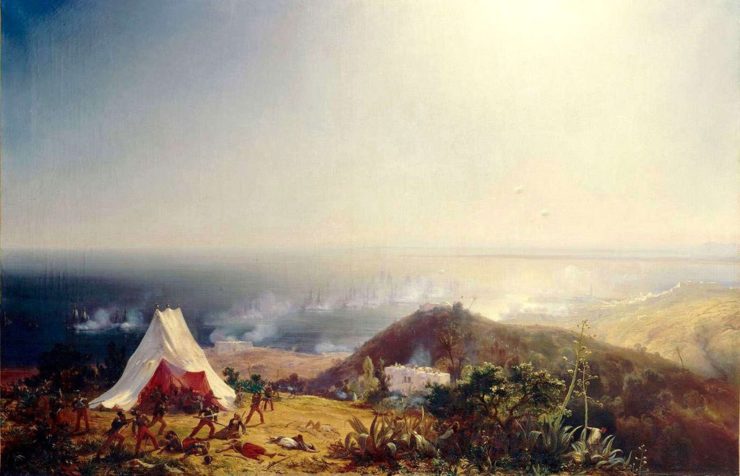

The lading of the French army. Théodore Gudin, ‘Attaque d’Alger par mer’ (1831). Source: Wikimedia Commons

A sculptured gaze

Of course, the surveillance work of the Chamber of Commerce in Marseille was not the sole instigator of the French turn to conquest. Domestic anxieties, geopolitical aspirations, crusading rhetoric and notions of civilizing benefits featured alongside the concerns over ships and cargoes. It would take until June 1830 before the massive invading army aboard its 700 ships finally set sail from Toulon. By then, the authorities of Algiers had already started manning the defenses, alerted as they were through the tested networks of information. A wealth of factors can be singled as influential in this chain of events, but the political usage of surveillance data was certainly one of them. As the great historian of the conquest Charles-André Julien noted, the arguments of Pierre-Honoré de Roux featured heavily in subsequent official rationalizations of the invasion. The board members of the Chamber of Commerce of Marseille also considered De Roux’s role to have been pivotal. In July 1830, just after the victory, they proposed to erect a statue of him, as a monument to the man who made the first public call for an invasion. The statue never materialized, but if it had, with its sculptured eyes permanently fixed on the sea, it would also have been a memorial to the long, troubled precedents of Mediterranean surveillance.