USHS Blog

From Istanbul to Vienna. Safely Cruising through Insecurity in the Early 1840s

In April 1841, Danish novelist Hans Christian Andersen (1805–1875) put a stop to his grand tour of the Eastern Mediterranean. There were several routes he could follow home, the most direct and safest leading ‘via Greece and Italy’. But Andersen was inclined to follow a more tortuous and insecure route: a steam voyage from Istanbul to Vienna.

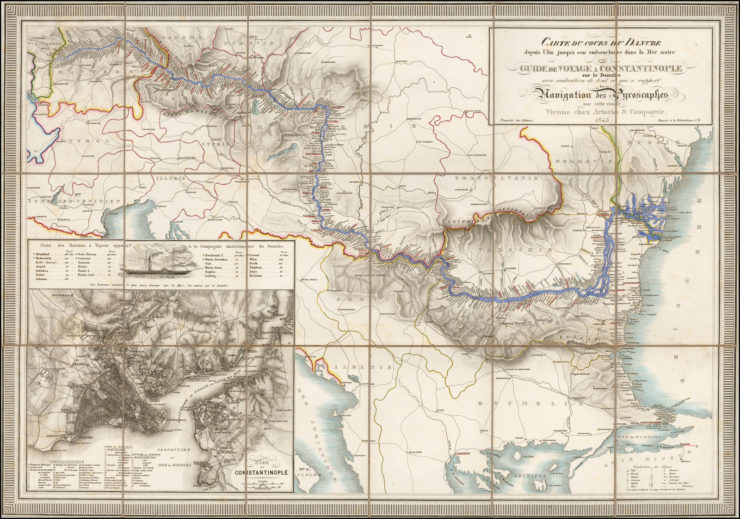

A Viennese company had introduced a steamboat service between the two imperial capitals in the mid-1830s, and the cruise was fashionable, picturesque, and adventurous. It was a perfect mix for a young writer in search of life experiences and literary inspiration. Advertisements of the trans-imperial voyage along the Danube noted not only the comfort onboard the state-of-the art steam packets, but especially emphasized the safe and timely conduct through this insecure and largely unknown corner of Europe. Safe as it was, the cruise was not short of perils, and Andersen’s travelogue, (A Poet’s Bazaar, published in Danish in 1842) takes readers on a passage through several overlapping layers of insecurity. This blog, following in the tracks of Beatrice de Graaf’s recent piece, ‘charts’ some of those insecurities, which Andersen discerned as he glided along the border of the Ottoman and Russian empires, towards the safer haven of a world he knew and understood: the Austrian Empire.

Hans Christian Andersen, 1869. Source: Wikimedia Commons

‘River of politics’

It took Andersen a month to complete the voyage from the Golden Horn to the Viennese Prater. Five steamers carried him towards his destination: one in the Black Sea and four along different sections of the Danube. The Danish poet had plenty of time to enjoy the pristine beauty of the Danube valley, but history and politics interested him as much and account for a large part of his narrative.

Since political and physical insecurity affected navigation through the Russian Danube Delta, the passengers landed in the small Ottoman port of Kűstendje (now Constanța, Romania’s largest seaport), where they changed for one of the river steamers. At Kűstendje, which displayed the scars of a troubled past, Andersen witnessed the first signs of the clash of empires along the Danube’s valley. The town had been destroyed by the Russians in 1809, but ‘everything appeared as if this destruction had taken place a few weeks ago’. It was an image of desolation which marked Andersen’s entire journey along this inter-imperial borderline. The crippled Ottoman fortresses of Silistria, Rusçuk, Widdin or Ada Kaleh were more proofs of the empire’s own insecurity and domestic crisis.

But there was a more immediate threat that worried the motley crowd onboard the Austrian packet. A revolt of peasants in Bulgarian and Serbian villages against Ottoman authorities had broken out in April 1841. The revolt, now known as the Niš rebellion, was only short, but the mist of rumors and uncertainty panicked the travelers. Only when Hussein Pasha of Widdin sent over ‘a large bundle of the very latest German newspapers’ did the passengers’ anxiety ease somewhat.

William Henry Bartlett, The Plains of the Lower Wallachia, from the Castle of Sistova, c. 1840. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Fighting the hidden threat

There were still greater threats looming in the East. The plague had been raging in Alexandria and Cairo, and sanitary officials were in full alert to fight its spread. The ‘Oesterreichisches Contumaz’ was famous for its severity, but the Ottoman, Wallachian or Serbian authorities were as strict. The steamer only called at the ports along the right (Bulgarian or Ottoman) bank, and harsh procedures were imposed to prevent any contact between ‘pestilential strangers’ and the local population. When the travelers disembarked and walked about in Widdin, they were properly ‘smoked through, so that the infectious matter in our clothes and bodies might be driven out’. On Serbian territory, local soldiers accompanied the voyagers and ‘took care that we should not come in contact with the inhabitants of the country’. Andersen eventually spent a week in the Austrian quarantine of Orșova, where even more armed guards defended the imperial border from its greatest and deadliest enemy: the plague.

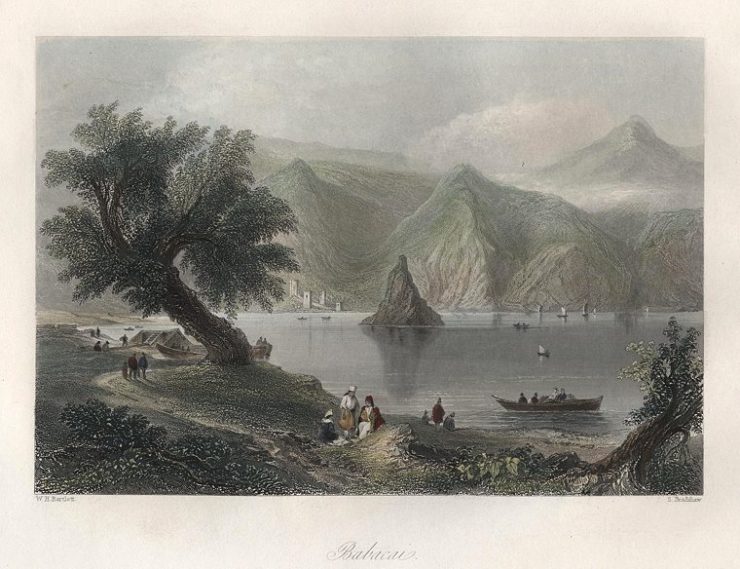

‘Babacai’, a rock in the Iron Gates area, engraved by S. Bradshaw after a drawing by W.H. Bartlett. Source: antiqueprints.com

Hydraulics and security

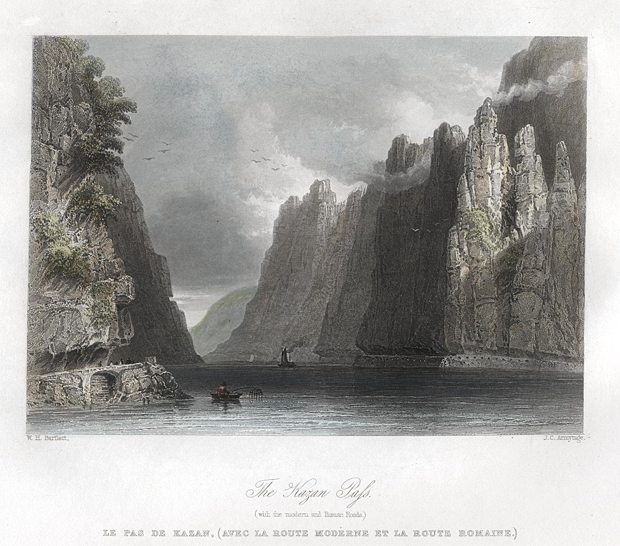

The river itself, still encumbered by watermills and sandbanks, also posed threats to navigation. The picturesque Iron Gates gorge, where the mighty river forces its way through steep mountains, proved particularly daunting. There, the Danube flowed over several reefs of rocks, and its ‘strong rapids’ and ‘mighty whirlpools’ often broke ‘vessels in pieces’. Andersen recounted a terrible accident of 1839, when the river capsized a boat full of cosmopolitan travelers ‘and every soul met a watery grave’.

Those insecurities were just then being taken care of. A Hungarian patriot named Count Istvan Széchenyi had started engineering works to tame the gorge in the early 1830s. To him, hydrotechnical improvements were vital for the progress of his nation, and he dedicated decades of his life to complete the costly works. Széchenyi sponsored the construction of a modern, macadamized highroad, carved into sheer rock on the river’s left bank, to ensure the immediate safety of passengers. This secured a continuous connection between the Lower and Middle Danube. With tunnels, bridges, and masonry work erected from the very riverbed of the Danube, travelers considered it a stone-hewn proof of security and civilization.

‘The Kazan Pass’ (the Iron Gates area) engraved by J.C. Armytage after a drawing by W.H. Bartlett. Source: antiqueprints.com

Civilizing the Danube

To Andersen, his journey was a rite of passage towards a world of civilization and security. The steamboat was a symbol of the modern world, majestically gliding through insecure quarters of Europe. Passengers exemplified the cosmopolitanism of the age of global travelling, with Western tourists, Austrian officers, and local aristocrats travelling in the more comfortable classes, while the deck was filled by ‘Turks, Jews, Bulgarians, and Wallachians’ who used the new mobility to search for better prospects in other corners of South–Eastern Europe.

Andersen’s bazaar of recollections remarkably captures the changing realities of Europe. His narrative is full of the lights, colors, sounds, and odors inspired by his Orientalizing stance and the memories of sweet Denmark. But it is equally full of references to how much the region was transformed by such technological innovations. Further changes would soon follow, as Austrians continued to engineer the river and its banks, constructing the area’s first railways in the 1860s. The Danube river came to serve as the primary infrastructure for the integration of these territories into the global market, a development that hinged on the security and predictability of the sort of steamers that carried Andersen and countless other passengers along the Danube.