USHS Blog

The ‘melancholy transaction’. Judging slavery and piracy in 1817

The law is one of those tools that could be a weapon, if it is just held right. Laws are the things that clad official policies, but they can also help to contest and set limits to those policies. A recent example is the ongoing back-and-forth of executive orders and court rulings over a U.S. travel ban. Concerns related to security only intensify that dynamic. Take the well-known practice of ‘function creep’, which involves officials stretching the limits of legal categories and articles to target increasingly more kinds of people and acts. Courts and judges can set bounds to those practices. At times with great effect. For the travel ban it is still too early to make such claims, but history can provide illustration and inspiration. Juridical sources of two centuries ago show us how the law limited ‘function creep’, though it was not an easy process. Historical records convey the human dilemmas that could mark the wielding of the law, especially when personal convictions clashed with legal reasoning. To get a sense of this, we need only return to a nineteenth-century day in court, when the crime of piracy – and its limitations – was the matter on trial.

Cape Mesurado, near to where the British Navy took the slaver Le Louis. Source: liberiapastandpresent.org

A piratical killing?

On 15 December 1817, London’s High Admiralty court convened right in the centre of the City, at a place called the Doctors’ Commons. The case on trial was, as the judge had it, ‘a most melancholy transaction’. It concerned a French vessel that had been taken by the British navy near present-day Monrovia. Setting sail from Martinique in January 1816, the Le Louis was headed for the coasts of West Africa on a routine expedition to buy new slaves, but ended up sailing straight into the historiography of international law. While the French crew was in the business of bargaining for enslaved people, it was caught in the act by a British navy vessel that policed against the trade in humans. A fight ensued as the Frenchmen tried to resist the arrest. Eight British servicemen were allegedly ‘piratically killed’. The Le Louis lost three of its crew, before it was captured and brought before a British court in Sierra Leone, which ruled the taking legal.

At an earlier time, this kind of capture could not have been imagined: it took place during peacetime and involved the subjects of a friendly nation. The unusual confiscation was inspired by contemporary ideas on international law and its enforcement, exemplified by the declaration on abolition of the 1815 Congress of Vienna. As part of their drive for an international ban on the slave trade, British officials had begun to equate the practice to piracy. Foreign Secretary Lord Castlereagh controversially tried to argue that slave traders were enemies of humanity, outlawed by all ‘civilized’ states. Like pirates, could they therefore not be prosecuted by any state?

The Doctors’ Commons on The Strand in London, where the Court of High Admiralty was seated. Source: WikimediaCommons

Blooded before the Admiralty

The case of the Le Louis had come to London when its French owners appealed the verdict handed down in Sierra Leone. The High Admiralty was the British Empire’s central court on all matters of maritime crime and the prize-taking of enemy ships, providing a constant stream of work that made the institute a financially attractive place to work at. On 15 December 1817, however, it faced the very fundamentals of international law: what allows one state to prosecute the subjects of another?

To the Crown’s Advocate, it seemed only ‘reasonable’ that the British navy could stop foreign slave traders. That reasonable policy had turned fatal here, but that did not alter its basic legitimacy. Both parties, he argued, ‘come into court with hands stained with blood’. According to Stephen Lushington, the defendant’s lawyer, the blood stuck to one side only: ‘that stain rests upon the captors who attacked, and not on the claimants who defended themselves.’ Lushington claimed the ship had been halted so far away from British jurisdiction as if it had been in ‘the middle of the Baltic Sea’ and maintained that the slave trade was not piracy. In effect, the men of the Royal Navy themselves had acted as a gang of pirates, using ‘mere lawless violence’.

Scott’s concerns

As he heard these dual statements, the presiding judge, William Scott, underwent a conflict of conscience. Having passed countless trials in his thirty years at the High Admiralty, this one appeared to him curious, singular and ‘melancholy’. He was an avowed abolitionist and repeatedly stressed his convictions as he read out the judgement. ‘Let me not be misunderstood, or misrepresented’, he said, ‘as a professed apologist for this practice, when I state facts which no man can deny’. Hence, ‘I must consider it, not according to any private moral apprehensions of my own (…), but as the law considers it’.

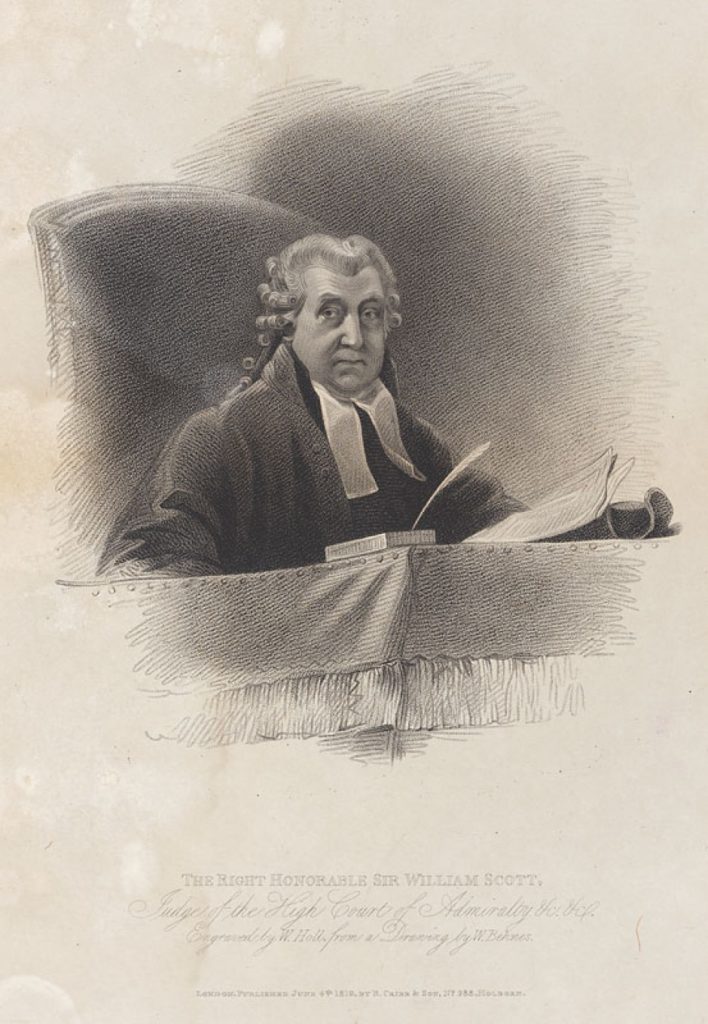

An engraving of judge William Scott. Source: Forskning.no

Scott was totally clear: the Royal Navy (and British diplomacy overall) had been at fault. ‘I answer, without hesitation, restore the possession which has been unlawfully divested: rescind the illegal act done by your own subject; and leave the foreigner to the justice of his own country’. The slave trade could not be deemed piracy, he concluded. It was not an act of indiscriminate assault that spread universal terror and alarm. Rather, it was an act ‘of persons confining their transactions (reprehensible as they may be) to particular countries, without exciting the slightest apprehension in others’. Britain had the naval power to enforce its abolitionist agendas, but this did not give it the right to usurp foreign property.

A law ‘dead born’

The ruling did not go by unnoticed. With that back-and-forth dynamics of law and security, it put British diplomacy on an altered track. The linkage of slave trading and piracy dropped from official rhetoric. Rather than trying to dictate a universal ban, the British government used bilateral treaties (with Spain, Portugal and the Netherlands) on the search and seizure of slave trade vessels. These were highly detailed agreements, so as to avoid other instances of ‘blooded hands’. The High Admiralty ruling thus helped revitalise thinking on the legal basis of anti-slavery, which unfolded in a context of patchy and vague international law. A law, furthermore, that still allowed to conceive of people as trafficable goods, simply on the basis of their origin. Yet, the Le Louis verdict contributed to a stabilising of abolitionist policies, putting them on surer and more secure footing. Earlier invocations of the law, which creeped in on the limits of piracy, had, as Scott ruled, been ‘dead born’.