USHS Blog

Counterinsurgency: The South African War (1899-1902) and its counter-effects

Counterinsurgency is a hot topic. Irregular wars have dominated contemporary conflict at least since the end of the Second World War. The sensed need for improved counterinsurgency strategies rose accordingly. Nonetheless, strategic thinkers and policymakers seem to be stuck between prioritising so-called ‘population-centric’ and ‘enemy-centric’ counterinsurgency methods. Whereas NATO forces in Iraq and Afghanistan prioritised engaging local people and helping them develop both socially and economically, enemy-centric critics state that all successes in Afghanistan can be ascribed to robust fighting both in the cities and the countryside. They argue that, in the end, only a campaign of attrition will lead to victory.

To weigh this criticism, the South African War of 1899-1902 provides an example and a particularly poignant illustration of how enemy-centric counterinsurgency strategies can have long troubled legacies. The British won that war with ruthless tactics of attrition, but at what cost? In military terms, Britain quelled Boer resistance within two years, but when I came across Boer minutes about the last phase of the war in the National Archives in Pretoria, it became all the more evident that British counterinsurgency stood at the basis of the turbulent country South Africa was to become. The material I found thus sheds new light on the legacies of counterinsurgency strategies.

A War of Attrition: The Seeds of Resentment

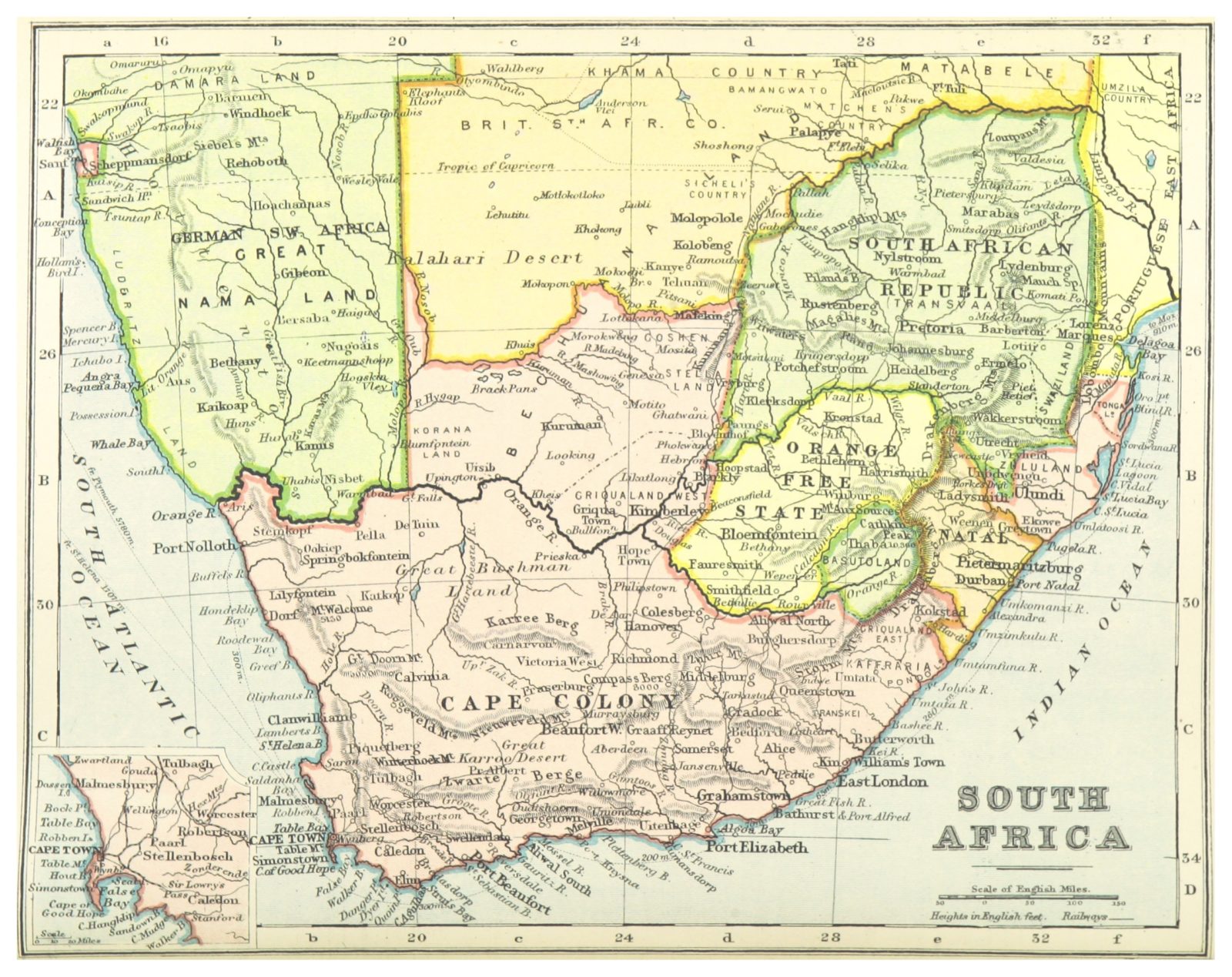

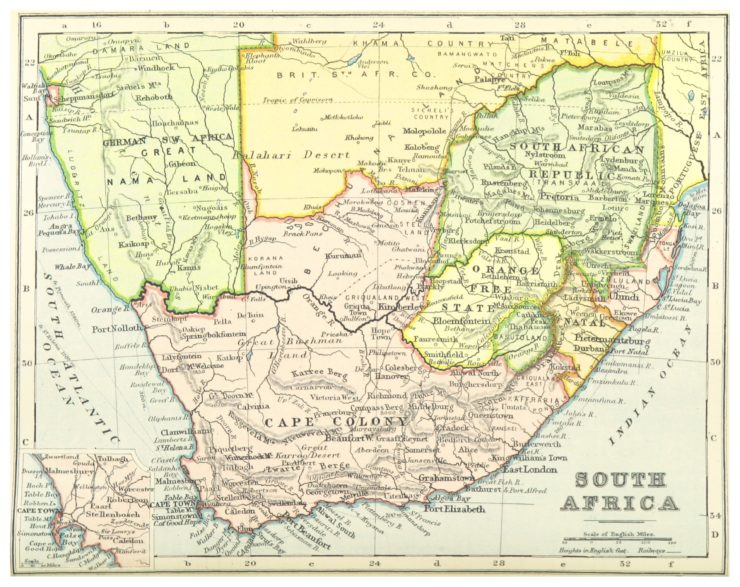

The South African War was fought between the British Imperial Army and the Boer people, descendants of the mostly Dutch colonists who settled South Africa from 1652 onwards. After Britain took over the Dutch colony in the early nineteenth century, the Boers left and moved inland to establish their own republics: the South African Republic (better known as the Transvaal) and the Orange Free State. Their very presence undermined British dominance in Southern Africa and war followed in October 1899, not long after gold was found in the Transvaal Witwatersrand mountain range. Despite initial Boer successes, Britain managed to break through Boer lines and conquer both republics’ capitals: Pretoria and Bloemfontein. Subsequently, the Boers resorted to irregular warfare in March 1900, using hit and run tactics to undermine British authority through ambushes, raids and sabotage.

South Africa prior to the War. The Cape Colony and Natal are British possessions. The Boer Republics are situated in the north east (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

British counterinsurgency policy quickly developed into a three-pronged strategy of attrition, centred on the principles of containment, scorched earth and internment. With the purpose of protecting the railways and expanding control of the countryside, British command ordered a refined system of blockhouses and barbed wire to seal off different sections of the South African terrain. British troops hunted the roaming Boer commandos within these sections and used a thorough scorched earth policy to prevent the population from supporting the insurgents with foodstuffs and ammunition. Countless houses and farms in the countryside were torched, leaving Boer families to the mercy of the open plains.

To control the roaming Boer population, the British erected concentration camps throughout the country. The camps offered only the most basic needs of existence and, as they came to harbour more and more people, conditions deteriorated rapidly. Twenty-five thousand people, up to fifteen percent of the entire Boer population, had perished before domestic pressure forced the British command to improve the abhorrent living conditions in the camps in late 1901.

The losses, alongside the shortage of ammunition and sustenance, brought the Boer leadership to sue for peace in 1902. The war left the country in rubbles. Britain had won the war, but at what cost? Destitute Boers returned to their farms only to find their houses ruined and their farmlands salted. They were deprived of their livelihoods and faced years of poverty and hardship. Consequently, hatred towards the British presence had settled so firmly into the hearts of a large part of the Afrikaner population that post-war reconciliation was all but obvious.

A Scorched Legacy: Resentment sprouts

In his post-war memoirs, Boer general Christiaan de Wet argued that the cruelties committed during the war by the British had led to persisting feelings of resentment among a large segment of the Boer population. These feelings brought forth a revival of Afrikaner Nationalism, which also manifested itself in anxieties over the Afrikaner people’s survival within the new South Africa. Put into perspective, this resentment and fear may have ultimately brought forth – as magnificently stated in ‘The Boer War’, by Martin Bossenbroek – ‘the ultimate illusion of safety’ found in the infamous policy of Apartheid.

Political strife followed not long after the war, pitching British loyalists against Afrikaner Nationalists. During the First World War, Afrikaner Nationalists rebelled against the government’s decision to fight Germany, one of the countries that had supported the Boer cause most dearly.

Although the rebellion was crushed by loyalist forces, the struggle continued in Parliament, where Afrikaner Nationalists united themselves in the National Party. Within the Afrikaner community, the concentration camps remained a shared, tragic memory and would form a historical point of reference for years to come. This historical memory was grist to the mill of the Afrikaner Nationalists, who vigorously held alive the idea of British responsibility for the marginalization of the Afrikaner people.

D.F. Malan, the first

National Party President

of South Africa (Source:

Wikimedia Commons)

Thus, when South Africa was drawn into a World War again in 1939, the nationalist movement’s propaganda brought anti-British sentiments to unprecedented heights, which led to a landslide victory for the National Party in the 1948 elections. Their victory formalised ideas of Afrikaner superiority and instigated Apartheid. The National Party furthermore steered South Africa towards withdrawal from the British Commonwealth in 1961 and remained in power until the first real democratic elections in 1994. The character of British counterinsurgency thus had a lasting influence on South African society and politics. Its legacy made itself felt as late as forty-six years after the end of the war. The South African War, therefore, exemplifies that enemy-centric counterinsurgency can backfire horribly and have a profound counterproductive impact, hampering reconciliation and cooperation for years to come. It is therefore clear that this part of history teaches us all the more that mere violence can never be a sustainable solution to insecurity.