USHS Blog

The State of Emergency, Part 2: The ‘New Normal’ in Counterterrorism?

Terrorist attacks can have destabilizing effects on societies. Not surprisingly, governments want a full spectrum of options to respond swiftly and effectively after attacks have taken place. One option is to call out a state of emergency. This creates a situation in which governments are permitted to perform actions that would not be permitted during a ‘normal’ state of affairs. That suspension of ‘normality’ is not something new. As our previous blog showed, France scaled up its counter anarchist legislation in response to anarchist violence in the late 19th century and called out a full state of emergency during the Algerian War of Independence.

For officials, a state of emergency or particular emergency measures may seem desirable, but for the public it may mean an abuse of power and an infringement of civil liberties. Since 9/11 in particular, several Western governments have responded to terrorist threats with new legislation, emergency measures or a full state of emergency. But what is the effectiveness of the ‘state of emergency’ in response to threats of terrorism and what are its enduring consequences? Is the ‘state of emergency’ perhaps turning into the ‘new normal’?

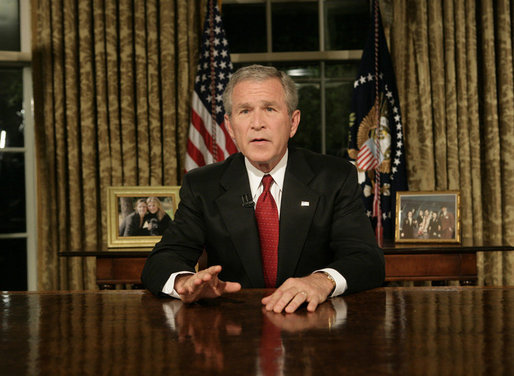

U.S. President George W. Bush in the Oval Office. Source: White House Archives

The War on Terror: enabled by emergency laws

On 14 September 2001, three days after the 9/11 attacks, U.S. president George W. Bush invoked a state of emergency. He declared: ‘A national emergency exists by reason of the terrorist attacks at the World Trade Center, New York, and the Pentagon, and the continuing and immediate threat of further attacks on the United States. (…) I hereby declare that the national emergency has existed since September 11, 2001 (…).’ Since then, Obama has renewed this invocation in both of his presidential terms. President Trump has not changed this either. Over thirty national emergencies remain in effect as of today. Proclamation 7463, for example, grants the President the legal opportunity to call up the National Guard for duty and to hire and fire military officers as the head of state sees fit. In response to 9/11, we have also seen the emergence of the Patriot Act, which has been highly criticized from a privacy point of view, and we have seen the notorious opening of Guantanamo Bay. Both measures have proven incredibly difficult to reverse.

The countries of Europe have also recently experienced a full state of emergency in response to terrorist attacks. The previous French president, François Hollande, declared France to be in a state of emergency on 14 November 2015, the day after the terrorist attacks in Paris. This state of emergency was also extended multiple times and lasted for nearly two years. Under the Macron government, the state of emergency officially ended on 1 November 2017, but critics noted that some of the exceptional counterterrorist powers have actually been turned into common law. In the new law, approved by the Senate on 18 October 2017, there are, for example, fewer limitations to house searches and house arrests. It also authorizes prefects to order the closure of mosques or other places of worship if preachers are suspected of praising or commissioning terrorist acts. The NGO Ligue des droits de l’homme hence denounced the new law because it ‘would trample individual and shared liberties and would lead us toward an authoritarian state’.

(in)Effectiveness and risks

States of emergency, wherever they are invoked, share some deep-rooted flaws and potential risks. In a recent report, a multi-disciplinary team of Utrecht University researchers analysed the political and societal consequences of the emergency measures in France, Belgium, and Germany, following terrorist attacks and threats in 2016. The research shows that emergency measures were implemented differently according to differences in constitutions, histories, institutional contexts, and cultures. However, in all cases it became clear that emergency measures, particularly when they are heavier and more all-encompassing, are not necessarily more effective in reducing threats of terrorism. A swift government response after an attack is imperative, but the researchers did not find clear evidence demonstrating that a full state of emergency, such as the one in France, actually decreased the terrorist threat.

Official toolboxes contain many more measures that may be more effective than the state of emergency. As the report emphasizes, various forms of emergency laws and measures exist, ranging from small adjustments to far-reaching interventions. In terms of counterterrorism policy, very specific and targeted measures, such as the improvement of early warning networks and long-term investments in de-radicalisation programmes, might be more effective than a full-blown state of emergency. More so, a highly performative state of emergency may very well have unintended side effects. A large presence of military personnel in public space, for example, can increase public feelings of unsafety. A state of emergency will have unintended effects on the perceptions of the public, and particularly on groups in society that may already feel discriminated against.

The ‘new normal’?

Is it a wise decision to call out a state of emergency in response to terrorist attacks? It could be effective, but also carries serious risks. It is paramount that the invocation should be proportional and remain temporary. Otherwise it may circumvent the basic standards of the rule of law. Yet, keeping an end date in sight proves to be particularly difficult. In a society under threat of unpredictable terrorist attacks, when is a government able to guarantee that the state of emergency is no longer necessary? Even though Macron ended the formal state of emergency, he did not reverse the additional provisions. The emergency measures turned into the ‘new normal’. As in the nineteenth-century example of our previous blog, the current legislation could well remain into effect for the next century or longer.

Sufficient checks and balances thus need to be in place. The Theresa May statement that opened our first blog, shows an explicit disregard for such checks and balances. Critical discussions on the state of emergency are the first line of defense of any liberal democracy. Keeping in mind the upcoming Dutch referendum on the updated intelligence law (WIV), it is as important as ever to critically reflect upon the checks and balances that are in place to make sure that the surveillance of the public by intelligence agencies is indeed effective, but at the same time proportionate. After all, once measures are anchored in legislation and made into policy, there might be no way of turning back.