USHS Blog

Security in times of plague and cholera

With the transportation revolutionin the nineteenth century infectious diseases travelled the world at an accelerated pace, and authorities used quarantines to contain, as much as possible, pandemic flows. In the 1830s, South–Eastern Europe witnessed the almost concomitant attacks of plague and cholera pandemics. This blog looks at how security measures against these transnational threats affected the sanitary, economic and political realities in the Danubian principalities of Wallachia and Moldavia. Quarantines were used and abused to contain the spread of dangerous political ideas, but they also stood at the basis of early transnational European cooperation.

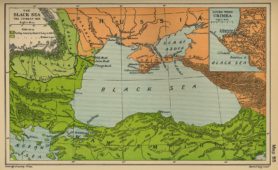

The Danubian principalities in the Black Sea area (1856) Source: Wikimedia

War and disease in the Danubian principalities

As the Russian armies entered the principalities in June 1828 at the start of a fresh war against the Ottomans, another scourge joined their ranks: the plague. Deadly epidemics had regularly ravaged this inter-imperial battlefield in previous decades, for example directly after the Napoleonic wars, until natural factors and sanitary measures kept the disease confined to more isolated villages where, in happy occasions, the plague would eventually die out. The war and its accelerated human mobility disrupted prophylactic policies, and the plague loomed large in 1829–1830. 26,302 civilians and 9,557 troops in the Russian army were the official death toll in the two Danubian provinces.

When peace was negotiated in Adrianople in September 1829, epidemiological concerns played a major role in shaping local political realities. Moldavia and Wallachia could ‘freely establish sanitary cordons and quarantines’ for the security of their subjects. Ottoman bridgeheads north of the Danube, regarded as pest holes for the spread of infectious disease, were returned to Wallachia, strengthening the principalities’ distinctive status within the Ottoman dominions. The quarantines were put to the test only two years later, when a cholera epidemic hit Moldavia and Wallachia, killing 20,218 people in 1831–1832. At the time when Moldavia and Wallachia did not have a regular army, the newly established sanitary corps served to protect them from all their enemies – foreign and domestic, macrobiotic and military. The principalities also served, in Russia’s sanitary and geopolitical plans, as an outpost for the empire’s security against Levantine pandemic threats.

The Moldavian–Russian quarantine of Sculeni (painting by August Raffait, 1837) Source: Wikimedia

Finding the proper balance between free trade and sanitary safety

The 1829 Treaty allowed the two principalities to enjoy ‘full freedom of trade’. With the introduction of steamboat navigation and increasing interest for Danubian grain, Moldavia and Wallachia entered the vortex of global capitalism. Too strict sanitary regulations were detrimental to business interests, especially given the different views on quarantines in Europe’s eastern empires.

The Lower Danube was a borderland of the Austrian, Russian and Ottoman empires, and each power employed different sanitary practices that further complicated the circulation of goods and passengers. Though they were privileged provinces of the Ottoman Empire, Moldavia and Wallachia adopted the Russian quarantine model. Cleaning practices for cargo and travellers in the Danubian outlets of Brăila or Galați included fumigation and the infamous spoglio (stripping passengers naked), while the position of chief inspector was usually saved for a Russian.

Other disputed quarantine practices derived from the diverging views of contagionists and miasmatics on the spread of plague and cholera. While no contemporary contested the epidemic character of the plague, cholera was considered an endemic disease that was transmitted under the influence of certain ‘atmospheric, climatic, and soil conditions’ better known as miasma.

At the Lower Danube, these medical disputes were translated into political and economic ones. For Charles Cunningham, British Vice-Consul in the Danubian port of Galați, quarantine was completely ineffective in stopping the spread of cholera. The principalities had managed to contain disease, but this had more to do with urban sanitation than with quarantine policies. Foreign consuls and merchants, most of them miasmatics, vocally contested Russian contagionism and overtly opposed quarantine procedures, which they regarded as deliberate impositions meant to limit grain exports from Danubian outlets.

The port of Brăila in Wallachia, 1840s (painting by Michel Bouquet) Source: Wikimedia

Political police in Danubian quarantines

There was something else that made quarantine stations a very intrusive and politicised institution. With the circulation of liberal ideas, especially in the 1840s, quarantines would also acquire the function of preventing the spread of contagious political ideas. For western travellers like Patrick O’Brien, a British agent who visited the principalities in 1853, the quarantine was ‘a polite incarceration of four or five days, during which the police have every necessary facility for making inquiries into your political opinions and your object in visiting the country’.

The quarantine was even more severe in the Danube Delta, a Russian territory where sanitary stations had replaced, for defensive purposes, actual fortifications. Pretending to care about its own and Europe’s public health, Russia was accused of having erected ‘fortresses’ that exercised control over its political and economic rivals. Under sanitary guise, Russia could stop commercial vessels ‘passing up the Danube to other states’ and detain them at will.

Transnational cooperation on quarantine regulations

Since the 1830s, as free trade in the Levant collided with stricter sanitary regulations, European governments insisted that further cooperation was needed to standardise preventive practices to fight disease. After the 1838 Balta Liman commercial treaty, agreements were sought to regulate quarantine measures. This led to the establishment of an Istanbul Superior Health Council (1839), which would coordinate sanitary measures taken throughout the Levant.

The push towards further standardisation led to the organisation of the first International Sanitary Conference, which opened in Paris in July 1851. For the coming six months, delegates from twelve European states with interests in Mediterranean trade and shipping convened in the French capital to exchange ideas on the medical and economic role of quarantines. Each country sent two delegates (a medical expert and a diplomat), who voted based on their expertise. Innumerable disputes followed and although there were little practical results, participants did manage to draft several documents which encouraged states to share knowledge and practices on fighting pandemics.

A European quarantine

It would eventually take a war to end Russia’s allegedly abusive quarantine practices. As the victors of the Crimean War noted in the 1856 Paris Treaty, the Danubian quarantines were to be reformed and put under international control. Fighting disease would no longer be a pretext for hindering free trade. The common fight of European actors against the spread of disease continued throughout the 19th century, as far-reaching treaties and shared practices were implemented in other places of inter-imperial interest like North Africa and Egypt. Standardised quarantine practices were increasingly securitised and institutionalised, featuring in further international medical conferences. Thus, plagues and diseases formed a more substantial base for international cooperation than evidently political security concerns ever could.