USHS Blog

Sailors versus steamers. Rhine disputes in the 1840s

In the nineteenth century, steam-powered boats offered a boon for commerce and navigation on the Rhine. However, in the 1840s, stakeholders, and especially those in the sailing business were not at all ready for these innovations. They felt highly threatened by the opportunities this new means of transportation provided to big capitalists in the shipping market. The fear of unemployment spurred by technological change on the Rhine was not much different from the fears that encouraged the Luddites to destroy textile machinery earlier in the century. Neither is it completely unlike the dystopian visions in today’s discussions about a job market overtaken by robots (check whether your job is at risk at willrobotstakemyjob.com). In 1848, amidst a wave of European revolutions, such anxieties led to an outburst of violence that brought steam navigation on the Rhine to a sudden halt. At this point, the Central Commission for the Navigation of the Rhine tried to intervene. Its attempt was initially without success, but eventually managed to aid both sailors and steamers, thanks to slow, sub-state and transnational diplomacy.

Steaming into the future

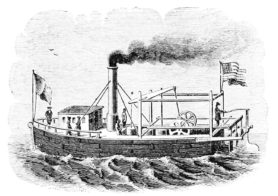

The first steam-powered boats appeared on French, Scottish and American rivers around the 1780s. It would take until the 1820s, after the necessary tranquillity had returned to the war-ravaged continent, before the invention was launched on the Rhine. Merchants, states and the emerging heavy industry in the Ruhr all regarded steam boats as a commercial blessing, as it greatly enhanced the velocity and regularity of navigation. Steamers were deemed a symbol of progress. They appeared in ever greater numbers on the Rhine from 1826 onwards, following a Dutch governmental decision to create a concessions-system for steamship companies. This was a unilateral move, but, as Dutch officials saw it, increasing transport activities was in the interest of trade, and thus in the interest of all.

At the meetings of the Central Commission for the Navigation of the Rhine (CCNR), officials from other riparian states spoke in similar terms of the positive developments steam shipping could bring to the Rhine. The French representative, Baron St. Mars, did raise one question: should the concessions not contain additional conditions to protect the small skippers? The large amount of capital needed to start a shipping company made the growing business inaccessible for the smaller entrepreneurs. The Dutch delegate, Johan Bourcourd, disagreed. An increase of transport speed was necessary to keep up with other trade arteries. Besides, Bourcourd argued, sail-powered barges still had their advantages. They were cheaper, and could, if organized well, also compete on agility, making them highly useful in carrying non-perishable goods. In the end, the delegates agreed that competition between the two industries would have a benign effect on Rhine trade as a whole and concluded that steam should continue without restrictions.

Tipping point

The CCNR’s conclusion turned out to be premature. In 1842, after the first steam-powered tug associations were established and the iron barge was introduced, the commission received dozens of reclamations from alarmed sailing skippers. ‘[T]oday, the battle is becoming increasingly threatening between the two kinds of transportation’, a sailor wrote to the French Commissioner: ‘and it is nothing less than the annihilation of an industry which will deprive many families of pilots, journeymen, apprentices and haulers of their means of existence’.

River transportation in the early 19th century barely differed from that in the 17th century, here painted by Salomon van Ruysdael. Towboat, sailboats and rowboat between Amsterdam and Gouda. Source: Allemaalfamilie.nl

The sailors argued that they were not against steamships as such. They were smart enough to know that they could not turn this tide. However, it was the way shipping companies applied the new technology that threatened sailors with redundancy. By towing large iron barges upstream swiftly and at an increasingly competitive price, steam boat companies entered the market of cargo transport that until then had been reserved for the sailing industry. While losing employment to the steamers was harsh, the prospect of a future Rhine industry that did not demand any of the sailor’s skills and knowledge was even harsher. Therefore, the sailors asked the Commission to limit steamboats to the transport of passengers and their personal belongings only.

Revolutionary spirits

Faced with these concerns, the CCNR devised several rules that were to aid the skippers against an oligarchic steamboat industry. Still, nothing substantial changed, until the Democratic Revolution of 1848 ignited the spirits of the shipmen, the pullers, and the shore dwellers whose property had suffered damage because of the large wave of steam boats. In the spring of 1848, they banded together and started to assault steamboats with guns. Franz Haniel, one of the large shipping company owners, wrote about one incident close to Weißenthurm: ‘One of my iron tugboats took 24 shots, yet was not fully penetrated. The helmsman steering the ship, who was usually the main target, had to be covered and secured by iron sheets.’ The rivalries were so serious that the steam service on some parts of the Rhine came to a complete halt. It was only after the authorities took military action that the towing services could be resumed. Intimidations nevertheless continued, while the large societal problem of a dying sailing business remained unsolved.

The CCNR as a dispute resolver

As the tumultuous events of the 1840s show, stakeholders regarded the CCNR as an authority in matters of Rhine navigation. Sailors and shipping companies approached the Commission to find a solution for a massive problem that actually went beyond its official mandate. By considering the fate of the sailors, the CCNR hence expanded its scope of action. It organized a meeting with representatives of both industries and tried to find measures that would retard the immediate extinction of the sailing business. Still, the room that the CCNR had to manoeuvre remained limited. A temporary stop on the growth of the steam-powered Rhine fleet was off limits, as was restricting the transport of cargo to boats with sails. Such action would go against the Mainz Convention of 1831 that guaranteed the freedom of navigation for all. Even the Commission itself was frustrated about the outcome, its president expressing ‘disinclination, because [the CCNR] only has authority to make suggestions, not to decide anything’ .

With the experience of this revolutionary year in mind, the CCNR decided it was time to turn over a new leaf. In the next two decades it effectively worked, within its mandate, to enforce the most liberal Rhine regime in which technological innovations were highly stimulated. Rather than realizing dystopias and bringing mass unemployment, the innovations resulted in an upswing of Rhine commerce and internal competition. Both steam boat companies and sailors would each have their raison d’être until far into the nineteenth century.