USHS Blog

Rumour has it. Fake news in 1815

In times of uncertainty, nothing matters so much as information. In Paris, after Napoleon’s defeat at Waterloo in late June 1815, rumours ran high. Napoleon had already escaped from exile and returned to France once, so couldn’t he a second time? For many contemporaries, everything came and went too rapidly to really comprehend: in quick succession there had been the Revolution, the Empire, an endless series of decisive battles, the Return of the Emperor, the 100-Days-period, and the Restauration of the Bourbons. In the midst of such accelerated times, what is more natural than for expectations, imaginations and strands of information to be generated at great pace? Rumours, fake news and hear-say were not just the news service of the weak, they also became the currency of authorities who struggled to get a grip on restive societies. The rollercoaster year of 1815 is thus a perfect showcase for investigating the interplay between the rumours that run around and the ways in which authorities try to get a feverish society back in check.

As excruciatingly difficult as it is to counter fake news today, the ‘fausses novelles’ of July 1815 were even harder to deflate or corroborate. In a fascinating article, French historian Pierre Triomphe has recently described the run of rumour mill at this time, when rumours did not only emerge spontaneously, but were fanned on by French elites, who sought to divert responsibility and accountability by discrediting the Allied occupation and the restored monarchy.

Occupied by rumours. Gathering intelligence in post-Napoleonic Paris

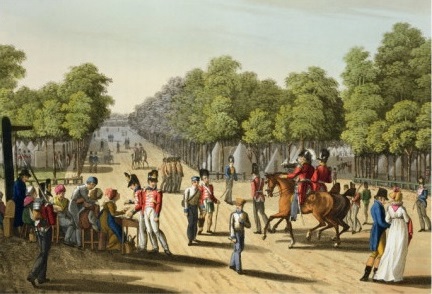

In 1815, Paris was occupied by the main Allied Powers of Europe. These powers did not intend to leave the city anytime soon. First, ‘the people of France’ would have to be brought back to ‘moral and peaceful habits’, as Foreign Minister viscount Castlereagh stated. Paris hence became a buzzing hub of all kinds of post-war activity. Dismissed veterans stalked the streets in search of employ, allied officers paraded the boulevards, and diplomats from all over flocked to the city.

‘Encampment of the British army in the Bois de Boulogne’, Paris 1815

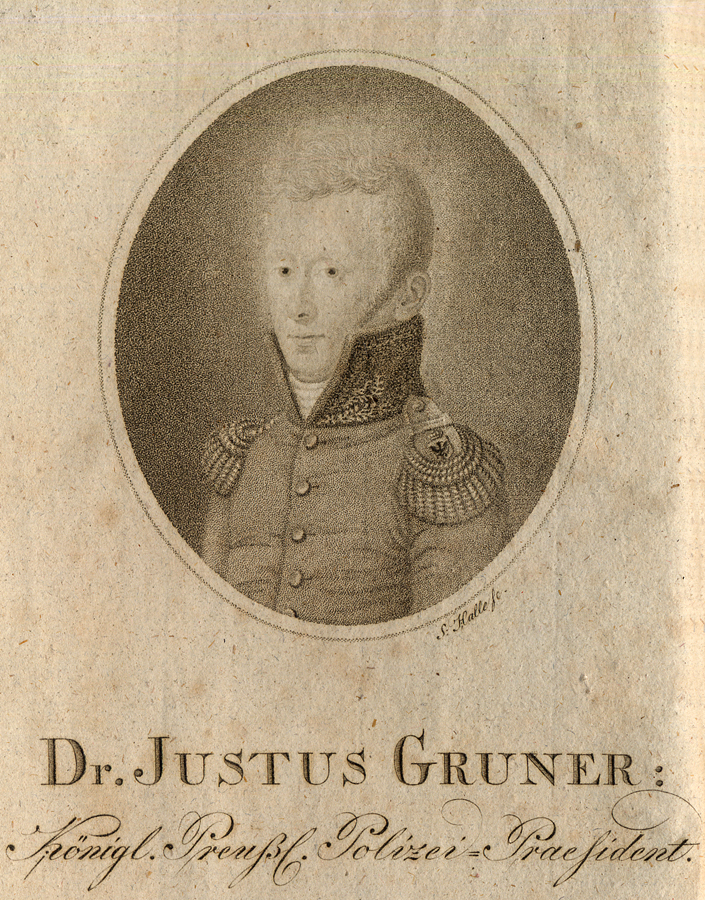

Paris turned into a marketplace of rumours and good information did not come cheap. Rumours (appearing in the sources as ‘bruits’ or ‘Gerüchte’) were being sold against sharp prizes as buyers were numerous. Authorities had come to rely on this type of intelligence since the days of the Revolution. The Prussian Justus von Gruner, the head of both the Allies’ haute police and military police, was tasked with amassing rumours on behalf of the occupying powers. Von Gruner had reformed the Berlin police and helped set up a spy ring for Tsar Alexander in Prague, so he was well versed in the business of intelligence.

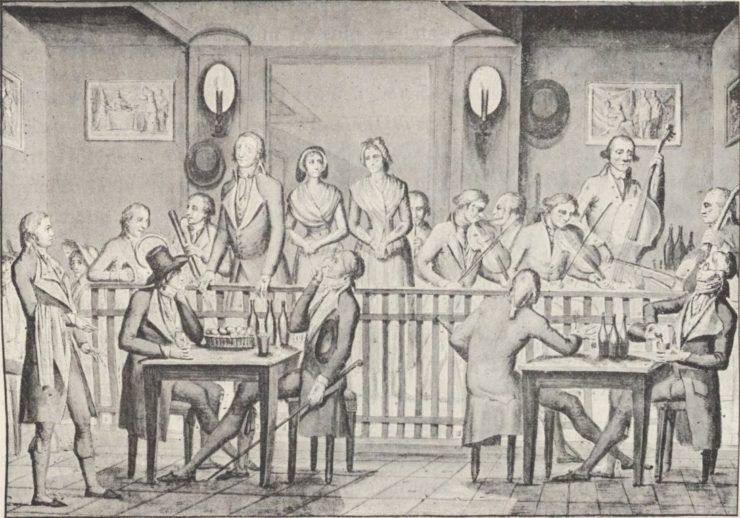

The Prussian chief hired a network of agents and compiled daily intelligence letters from their reports, listing events, incidents, attacks, and infringements upon the troops and public order. Every report contained a section on ‘Gerüchte’ as well, which was assembled through informants at the Café des Aveugles, the Café des Étrangères, on the Boulevards, and in the many hotels and salons in- and outside Paris. These reports provide a fascinating window into the preoccupations of the day. Gruner and his spies meticulously described the hearsay on Wellington’s escapades, alleged divisions between the Austrian and Prussian ministers, and rampant anti-Bourbon sentiments. According to Gruner, satire of the Bourbons circulated widely while exclamations of ‘Vive l’empereur!’, or ‘vive le petit Napoleon’ could be heard on a daily basis.

Café des Aveugles, Paris, source: WikimediaCommons

Words that kill. Beyond the hoax

The ‘rumour intelligence’ of 1815 fished in a deep and murky pond of public fears, panics and conspiracy theories – many of them rooted in Revolutionary experience. In his La Grande Peur de 1789, Georges Lefebvre described how aristocrat and royalist fears for brigands and multitudes travelled the country, while Bonapartists, liberals and moderates spread moral panic regarding ‘white terror’ and transnational ‘aristocrat conspiracies’.

Fake news thrived amidst mounting fears, lingering anxieties and sometimes very real incidents. The Allied Powers lacked the possibility of quickly verifying stories as correspondence with the provinces could take two to five days, so rumours often had to be reckoned with. Some of them were just plain ridiculous and could be discarded swiftly. At one point, a story made the rounds through the Paris cafés on the ransacking of Berlin by an ‘army of a thousand Turks’. Hearsay of immanent attacks on King Friedrich Wilhelm III or Louis XVIII, however, had to be investigated – even if they turned out to be a hoax.

Justus von Gruner, source: Rheinland-Pfälzische Personendatenbank

Information is key in times that were as ridden with anxieties as the year 1815 was. Yet when there is no legitimate authority at hand, there is no place from which to begin looking for that needle of truth in haystacks of rumour. Marc Bloch explained as much in his essay on wartime ‘fausses novelles’. Bloch wrote about his experience in the trenches of World War I, but in post-Napoleonic French society any claim on information-sovereignty was obsolete too. Von Gruner even lamented that French statesmen, especially Prime Minister Talleyrand, actually tried their hardest to create division between the Allies by means of spreading rumours, thereby further engendering discord and unrest within the country.

Accountability and trust

The Allies and the French each had to make do with rumours and conspiracy stories in the end. Von Gruner argued that the circulating rumours showed just how badly the French citizens were informed of ongoing affairs. Yet the rumour mill also unveiled the inability of King Louis XVIII and the Allies in offering to the French what they really needed: authenticity, legitimacy and trustworthiness at the head of their country. Only after Talleyrand was supplanted by the Duke of Richelieu, who was renowned for his honesty and integrity, the French found a leader who offered them that sought-after rarity: a genuine, truthful explanation of the bitter fate the French had to suffer. The Allied occupiers went home in 1818 – rumour did persist afterwards, but its preponderance gave way to printed, accountable policy and public debate.

The author is currently working on a monograph on the Allied Council in Paris, between 1815 and 1820; this blog is an excerpt from this work, based on archival sources from Berlin, Londen and Paris, amongst others.