USHS Blog

The Rhine during the Napoleonic Empire: a tourist perspective

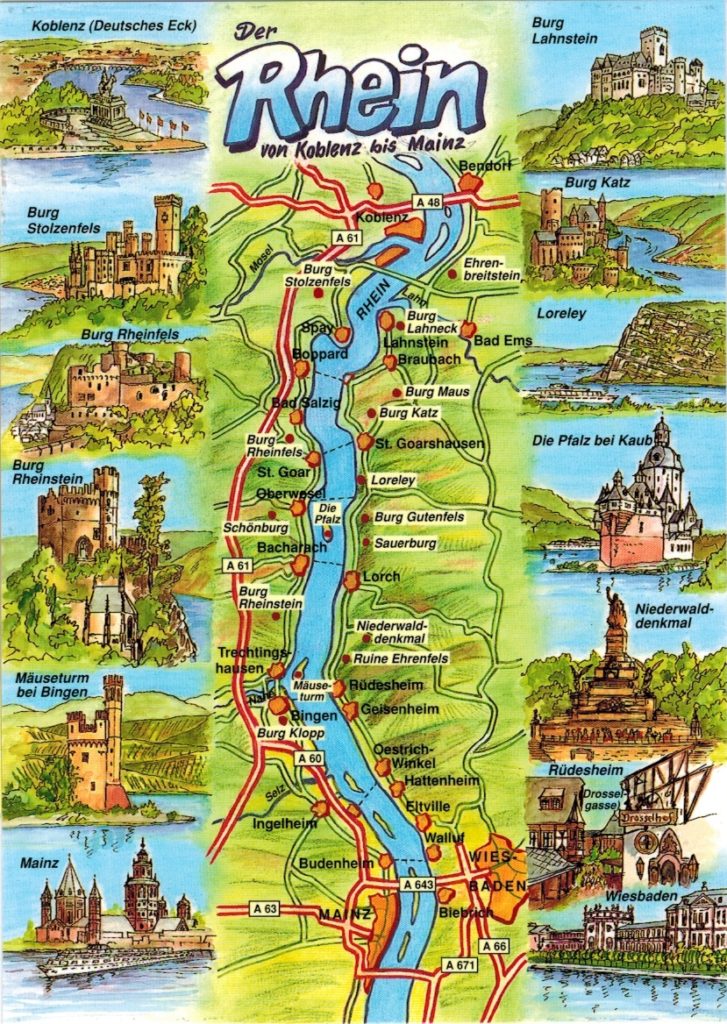

The romantic castles, hilly vineyards and historic towns between Bingen and Koblenz attract millions of visitors each year. Indeed the Rhine River Valley, part of Unesco World Heritage, is one of the prime tourist destinations in Germany and Europe today. When the French ruled the area in the reign of Napoleon, they saw the Rhine as anything but a fancy tourist site. Above all, they considered the Rhine a three-layered border. That is: as a former military border; as an economic border that was strictly guarded and tolled, and; as a porous political border, which delineated areas under direct, strict French control (the left bank) from those under more free client rule (the right bank). Despite all these borders, the Rhine nevertheless became a fashionable tourist route already during the Napoleonic era. A travelogue of a famous Dutch politician gives us a taste of the local communities’ daily life and of and the region’s tourist potential under French rule. In this blog, we follow him on a journey of three stages: from misery to economic potential to casino capitalism.

Cologne: a ghost town on a river in chains

It was in the late summer of 1811 when Anton Reinhard Falck caught up with two friends in the French Rhine city of Cologne. Falck was a legal expert, and held various positions in the succeeding French governments of the Netherlands. This first stop on his journey seemed depressing to him. Cologne was too empty, too old-fashioned and too gloomy for Falck’s taste. When he observed the graveyard just outside the city, he concluded ‘(…) that the people from Cologne were housed quieter and more enjoyable after their death than in life.’ The only reason that there were no beggars, Falck noticed, was because the French had dissolved all monasteries (the places where beggars and homeless found a last refuge) and had all vagabonds employed in forced labour.

An important reason for Cologne’s economic downturn was the French treatment of the Rhine as a strict commercial border. It had been shut off for English commerce and fallen victim to the repressive forces of the Napoleonic customs regime. Falck despaired: ‘(…) who liberates us from the Customs officers? That wonderful product of modern day government, much more damaging to industry and honesty than medieval monasticism to true virtue and enlightenment, shows itself to the Rhine in full glory.’ Day and (especially) night, hundreds of officers were collecting tolls and were watching the river closely. The system had rooted out smugglers recklessly, but had suffocated the once vigorous Rhine trade as well. ‘Miserable systema!’, Falck noted. ‘Miserable fate of a stream which the beneficent nature had intended for a means of communion and of reciprocal civilization, for the multiplication of the enjoyment of twenty peoples.’

Koblenz and Mainz: freed from a military burden

For years, the cities along the Rhine had been on the military frontline, but that had changed by 1811. The expansion of the French empire towards the east meant that some river towns recovered remarkably well. Under French hegemony, the Rhine had become much less of a military border. Falck observed the consequences of this development in Koblenz, a town that was more to his liking. ‘There is movement going on, in the streets, yes, even in the port. The ferry runs continuously until 10 in the evening, whereas the one in Cologne had 30 minutes break after each run and already stopped running after 9:30.’ This movement and the ensuing growth of prosperity were initiated when the French conquered and annexed the city, removing all of the fortifications. ‘Those good people are now free from carrying the burden of a heavy garrison as well as from the fear of experiencing months of dangerous sieges, as in 1796 and 1798.’

The disappearance of the military border had less of a healing effect in Mainz, the next stop on the journey. The ruins of the 1793 bombardment were still visible. Moreover, the flight of the nobility and the disappearance of the high clergy from this town to other, German side of the Rhine, had left a clear demographic vacuum. The remaining French troops hardly filled the deserted streets.

Frankfurt: a city to try one’s luck

Besides perceiving it as a military and commercial frontier, the French also regarded the Rhine as a political border. All territory on the left side was under direct rule of the First French Empire. The lands on the right side belonged to client states, which had some political autonomy. That autonomy was easily notable in the first large city that the Dutch travellers visited on the Rhine’s right side: Frankfurt am Main. Falck and his friends were immediately enchanted by its enormous and continuous bustle. As in Koblenz, the city walls had been torn down and new city gates and lanes were in the making. ‘Airy iron fences with guard houses on both sides, whose architecture is very elegant, I like it, whatever the lovers of the old may say, much more than the dark covered passageways, which the idea of a military defence formerly made necessary.’

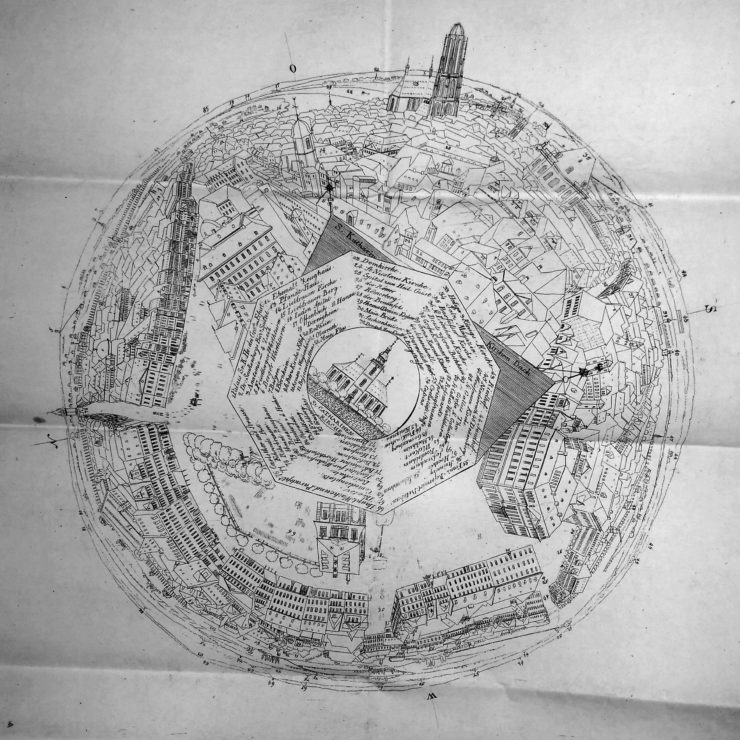

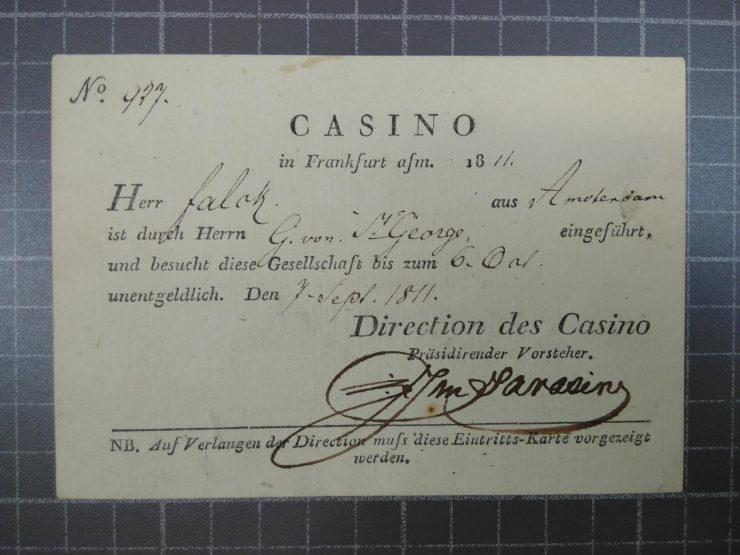

The map above, held in Falck’s archive at the Dutch National Archive, proves that tourism was an upcoming thing in Napoleon’s empire. Frankfurt was clearly well prepared to welcome visitors like him. The map, which gives an overview of the city as if on the roof of St Catherine’s Church, shows churches, plenty of hotels, and squares with nice fountains. It even lists a casino, which Falck, as a ticket of entry in the same archives discloses, certainly did not renounce to visit. Falck noticed that the people seemed happier. In comparison to the inhabitants of the left side, ‘(…) they are not checked in all acts of bourgeois life, guarded, and harassed and tormented by all kinds of ordinances (…).’

That relative liberty and the absence of military action awakened private enterprise, created room for modern urban planning and inspired architectural beauty. The basis had been laid for a flourishing industry that now mainly draws cruising seniors rather than adventurous youngsters, but which still benefits the region – on both sides of the Rhine.