USHS Blog

The Price of Security. The Dilemma of Paying for Peace (in 1818 and 1919)

What is the price of security? Can money pay for it at all? The answer could very well be negative, especially when we consider the upcoming centennial of the Paris Peace Conference and the Versailles Treaty of 1918-1919, which was a source of radicalization to disgruntled Germans. However, there is another, very much forgotten, jubilee to celebrate next year, offering totally different insights. In 1818, at the Congress of Aachen, the victorious allies (Russia, Prussia, Austria, Great Britain) reviewed the post-1815 peace that was paid for by France – thereby heralding in a new era of collective peace and security in Europe. Both anniversaries offer proof of how the security/finance trade-off is at once historical and problematic.

William Orpen, ‘The Signing of the Peace in the Hall of Mirrors, Versailles’ (1919). Source: Wikimedia Commons

Costly wars

Take the costs of war. War not only upends economies through endless fighting, draining of resources, or organized pillaging and looting, it also incurs costs after the battles are over. Not just for the defeated, but for the victors as well. Defeated or occupied countries were therefore to pay in some way for the wartime losses induced. That is how the concept of ‘reparations’ gained traction. Since the ancient Sumers, Greeks and Romans, the idea of victory centred on making the defeated party pay for the war, and issue regular tribute to the victor. However, instead of producing security, these tributes were often considered a just cause for renewed war. The relationship between payments and security was thus a rather threatening one, quite similar to extortion: ‘pay us or we will attack you’. Almost two thousand years later, Napoleon took this kind of extortion to a new level of legalized ruthlessness. With the Treaty of Pressburg, for example, he used international law to not only strip Austria of one-sixth of its territory, but also obliged the country to pay indemnities amounting to 40 million francs.

According to historian Paul Schroeder, these classical forms of war tribute were absorbed and accommodated into the new system of ‘balance of power’ that started to govern international relations in the 18th century. Amongst the new mechanisms to manage that system were legally sanctioned compensations and indemnities. These were not just taken at random or as crude tributes, but as a means of enforcing compliance with the victor’s take on the international system – and as deterrence for stepping out of an alliance.

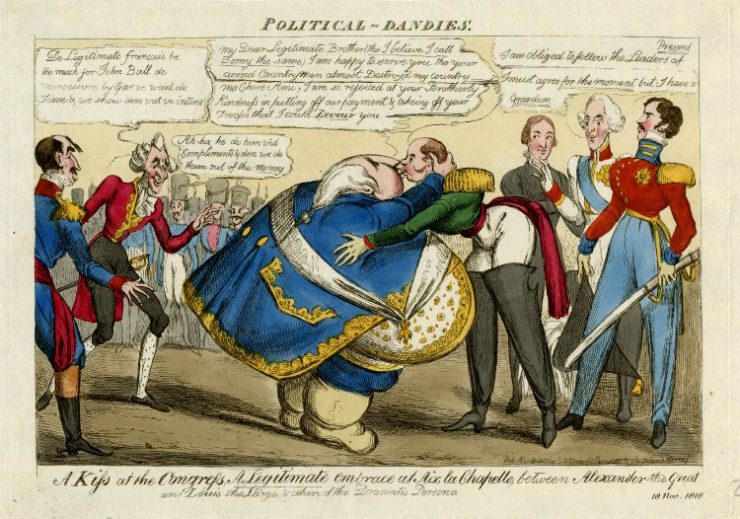

Cartoon ‘A kiss at the congress, a legitimate embrace at Aix-la-Chapelle’ (1818). Source: British Museum

A peaceful payoff

Against this historical backdrop, the 1815-1818 spell of collective peace making after the Congress of Vienna was even more revolutionary. The victorious allies indeed decided to impose reparations on France, but not in the classical Roman, or ‘modern’ despotic interpretation of Napoleon. Rather than imposing reparations as punishment or revenge (as the Prussians briefly suggested in the summer of 1815), the allied ministers concluded a treaty, the Treaty of Paris, that developed a truly different perspective on the security/finances trade-off. For Castlereagh, Metternich, Tsar Alexander (and eventually also for Hardenberg), the payments France had to make served European security first and foremost.

Of course, some sort of sanction for Napoleon’s violation of the 1814 treaties and the Hundred Days had to be put in place, as well as some sort of redress for the allied campaigns and enduring occupation of France. Still, the final sum of 700 million francs of indemnities was quite moderate. The reparations were conceived not merely as a sanction, but far more as an impulse, a leverage to allow France to pay her way back into the system of ‘balance of power’ as a respected ally. Another novel part of this arrangement had been the decision to temporarily occupy France, which Castlereagh called a ‘security to the Allies for their punctual Liquidation’.

The importance of the Congress of Aachen was provided by the assessment of this payoff, leading to the pull back of the occupation troops. How had France been able to achieve that feat? Interestingly enough, the collective security system at the time depended on an emerging new arrangement of international or transnational financial securities (e.g. financial instruments such as bonds, loans and obligations). As Glenda Sluga has pointed out, the post-1815 European security settlement also rested on the investments mobilized by the European banking houses of the era, which employed various informal ‘diplomats’ to assist the French in procuring a series of big foreign loans. By means of these loans, the French treasury was able to pay the sum of 700 million francs of indemnities, the 360 million francs per annum for the maintenance of troops as well as the claims for the liquidation of private debts. France eventually paid a total of 1,893 million francs. That sum was less than the reparations imposed on Germany after the First World War, but in absolute terms more than any other externally imposed war debt in the nineteenth and twentieth century.

Congress memorial in Farwickpark, Aachen. Source: Wikimedia Commons

The legacy of Aachen

The lessons of 1818 have grown stale, and forgotten. The last 200 years are a historical graveyard of failing and contradictory experiments in the domain of producing security by means of financial leverage. Without delving too deep into the war reparations of 1918/1919, one can safely argue that the Versailles stipulations were predominantly intended to reap the spoils of war and simply gain booty. U.S. President Wilson, like Castlereagh and Metternich in 1815-1818, based the reparations on the defeated country’s capacity to pay and was willing to shorten the period of payment. Yet France decided to invade and occupy the Rhineland in 1923 as a sanction of the Weimar Republic’s defaults. History quite consciously did not repeat itself in 1945, when the western allies came up with the Marshall Plan. The Soviet occupation regime, on the contrary, continued the tradition of tributes and organized looting instead, thereby transplanting the last remnants of political security with the Orwellian security of dictatorship.

With an eye on the 2018-2019 centennial of the Paris Conference, it may be illuminating to focus on the practice that overshadowed bicentennial, of the Conference of Aachen. There and then, financial securities where indeed used to procure a secure peace, and served to lift up the defeated country, rather than cause further ruin. But for such a security/finance trade-off to work, a constellation of benevolent, moderate statesmen, international arbiters and reliable bankers and diplomats is essential, and not to forget: a compliant defendant. These are not things that history hands out generously.