USHS Blog

Mobilizing the Brain: International Rivers and Knowledge Production at the End of World War One

In 1917, the minister of education in David Lloyd George’s government, H. A. L. Fisher, duly noted that the war had become a ‘battle of brains’, and researchers of all disciplines were ‘powerful assets to the nation’. Chemistry, physics or biology had been mobilized since an early phase of the conflict. It was high time for the humanities to fully join in the intellectual combat for a better world.

Historians or philosophers had already been involved in winning hearts and shaping minds for the patriotic cause in humanity’s greatest struggle yet. Now they had to contribute to the production of knowledge for the future peace congress. Eventually, the war would be won with state-of-the-art military equipment and greater economic resources, but at the coming peace congress diplomatic triumph would side with those relying on the readiest and most accurate information.

As state departments got ready for diplomatic confrontations and legal disputes with friends and foes alike, scholars in the humanities offered their expertise. Philosophers insisted that it was vital to set out the moral principles for a new and just world order. Historians, linguists, geographers and jurists promised to produce accurate accounts in their fields of study that could help settle the myriad of remaining disputes, especially concerning a particularly salient bone of contention: rivers.

Academic centers for the production of expert knowledge

In France, in February 1917, the country’s most eminent professors (mostly historians and geographers) grouped together in a ‘Study Committee’. Headed by historian Ernest Lavisse, the committee brainstormed on the world’s most pressing questions and started to prepare handbooks for the confidential use of the French diplomatic negotiators. They looked to close detail at subjects as diverse as the partition of Poland, the making of the Slovak nation, the borders of Balkan states and the situation of the Armenian minority in the Ottoman Empire. In all these, they tried to accommodate local aspirations and French interests.

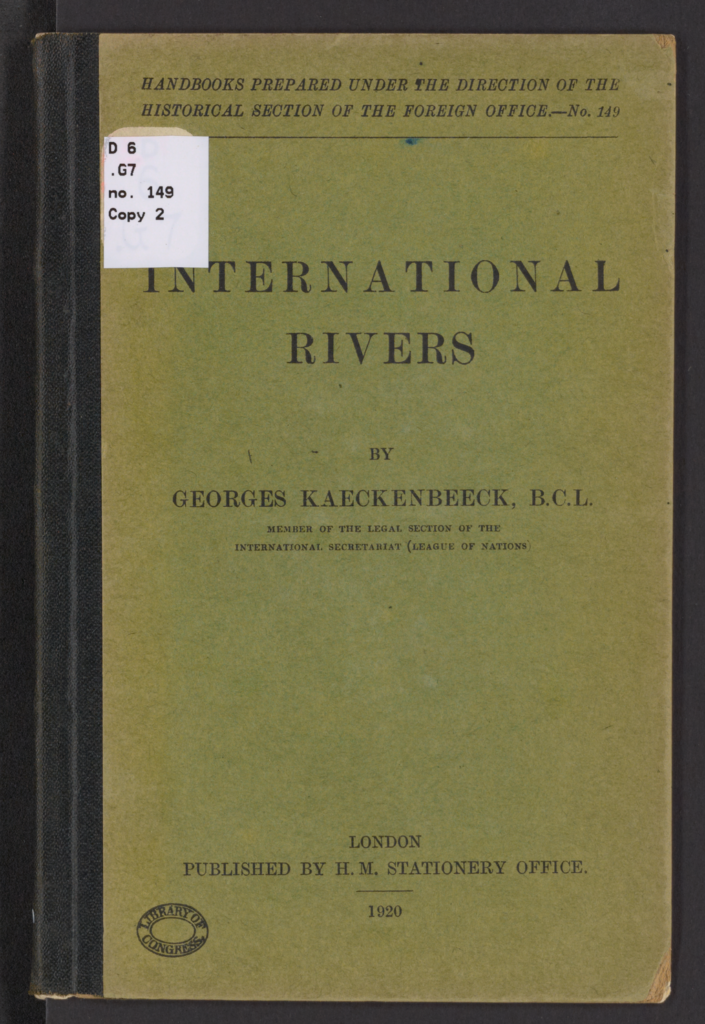

Britain established a similar institution, also led by a historian: George Prothero, the former editor of the Cambridge Modern History. This ‘Political Intelligence Department’ (PID) authored 174 volumes on various territorial disputes, national questions or border settlements with which the British delegates to the future peace conference might have to deal. For Harold Temperley, one of the most celebrated diplomatic historians of the 20th century, militant scholarship in the PID was the best way of serving both his country and his academic discipline. Illness prevented his participation at the Gallipoli landings, but he hoped that his confidential reports to the Foreign Office and his published volumes on the national questions of the Balkans would contribute to making a just peace in South-Eastern Europe.

The United States created the ‘Inquiry’ in 1917. Over one hundred distinguished scholars were gathered to defend their national cause by collecting, organizing and synthesizing critical information for the use of American diplomats. Each of these academic centres relied on vast networks of experts and had access to the best research resources available in those times, like the reading rooms of the New York Public Library or the offices of the American Geographical Society. The Inquiry’s activity was divided into five fields of analysis, representative for their internationalist approach to the new world order: the powers (friends, enemies, neutrals), debatable areas and unfortunate peoples (from Alsace-Loraine to the Jews and the nationalities of Eastern Europe), international business, international law, and international cooperation.

‘Experiments in international administration’

Historians, geographers and legal experts in all these committees paid special attention to rivers. The commissions that regulated navigation along Europe’s largest two international rivers, the Rhine and the Danube, were assured of expert attention. Both waterways had been bones of contention between states during the previous centuries, but disputes had been largely resolved by remarkable instances of international cooperation. For the proponents of internationalism, such as political scientist Leonard Sidney Woolf, river commissions provided the first example of ‘deliberate international legislation’ and led to the ‘creation of the first international executive in the Danube Commission’.

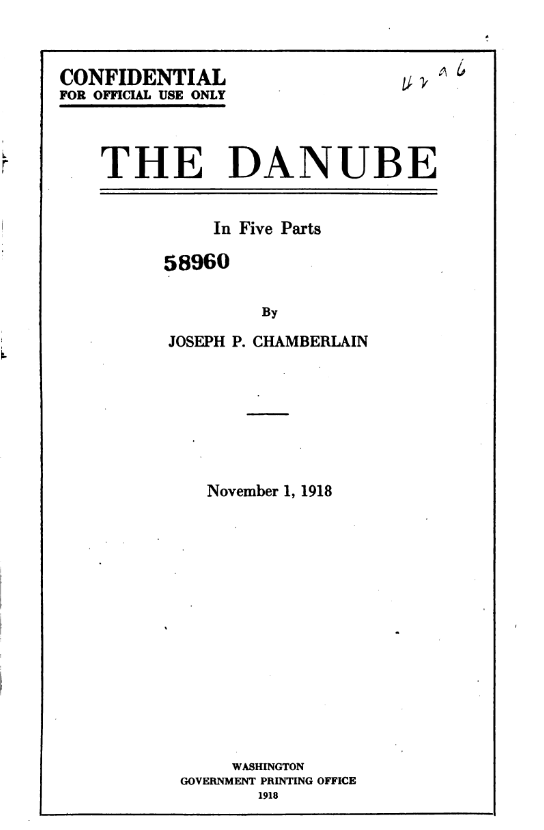

In Paris, London and New York, scholars wrote handbooks on the history and legal status of the Rhine and the Danube, and advertised river commissions as functional organizations for all of the world’s transboundary waterways. Edward Benjamin Krehbiel, a historian working for the American ‘Inquiry’, believed that international river commissions endowed with large executive attributions could limit national jealousy and thus create a more peaceful and secure world. To him, the Danube Commission was ‘the most ambitious and the most successful experiment in international administration’. Hence it was worth being transplanted to other rivers and canals. Joseph Chamberlain, the author of a handbook for the use of the US Department of State, equally considered that the Danube Commission was ‘an agency of the Great Powers, indeed of the Concert of Europe’. To him, this proved that international cooperation in pursuit of common interests was possible. Similar ideas were entertained by legal expert Georges Kaeckenbeeck and historian Émile Burgeois, the European experts tasked to deal with the analysis of international rivers.

Experts at the Peace Conference

The experts’ involvement in producing knowledge proved extremely useful during the Paris Peace Conference. As an author mentioned, when the negotiations started in 1919, the American delegation was equipped ‘with approximately 2,000 separate reports and documents covering about every subject likely to arise for discussion and many that were not’. Moreover, they had at their disposal ‘a series of definite recommendations for the solution of many thorny questions’. For another, ‘the more lasting results are contained in some (too few, alas!) of the terms of the peace treaties, for it was from the Inquiry that the technical staff of the American delegation to Paris was largely drawn’.

Returning to the Rhine and Danube commissions, they served as models for the establishment of similar international organizations on other transboundary rivers. Legal expert David Hunter Miller, a member of the Inquiry and one of the American delegates in the Commission on Ports, Waterways and Railways, repeatedly referred to ‘the well-known precedent of the European Commission of the Danube’. The Paris Peace Conference served as a stage on which such knowledge could be mobilized, not as an auxiliary to war, but as a harbinger of peace.