USHS Blog

ISIS Cells and Anarchist Leprosy. Is there a Cure for Terrorism?

A Dutch F16 pilot employed in Jordan recently compared the fight against ISIS to the surgical removal of a disease: “If a few cells remain, they have the strength to make one ill and expand; if not eradicated, they will continue to develop.” Analogies drawn between terrorism and infectious diseases are nothing new. In different times they have appeared in highly similar forms, helping to bring order to a complex issue and allowing people to grasp what is otherwise incomprehensible. The analogy surfaced especially in the late nineteenth century, an ‘epoch of unprecedented technological advance’, during which science could ‘transform civilization and change perspectives’. Discoveries in microbiology and the containment of diseases had a significant impact on everyday life, as did sociology and social science with the gathering of data and statistics. The different discoveries were also combined and applied to other new political phenomena like modern, anarchist terrorism – including dangerous connotations, particularly in now suspect and commonly denounced corners of science, such as social Darwinism and eugenics.

Terrorism, moreover, was not only compared to contagious diseases as a metaphorical means of understanding a problem. It was thought that newly gained epidemiological knowledge provided a constructive solution to the issue of the terrorist threats too. How and why did this idea arise in the late nineteenth century? What sort of ‘cures’ were conceived of? And what does their impact on the suspected ‘patient’ tell us about present-day analogies?

‘The anarchist leprosy’

Modern terrorism has been presented as a contagious disease at least since its emergence in the 1880s. The intensity of the violence carried out by anarchists was seen as unprecedented, notably because local outbursts were seen as part of a global conspiracy. In attempts to explain the violent events of the time, policymakers and newspapers drew comparisons to other issues that also spread around the globe and claimed the lives of many people. In the early 1890s, the Austro-Hungarian ambassador in Paris hence spoke of ‘the anarchist leprosy’. Alongside the understanding of anarchism as a contagious disease came suggestions to cure the epidemic. Criminologists and politicians presented solutions in two shapes: improving the immune system and removing or preventing the entrance of infected cells.

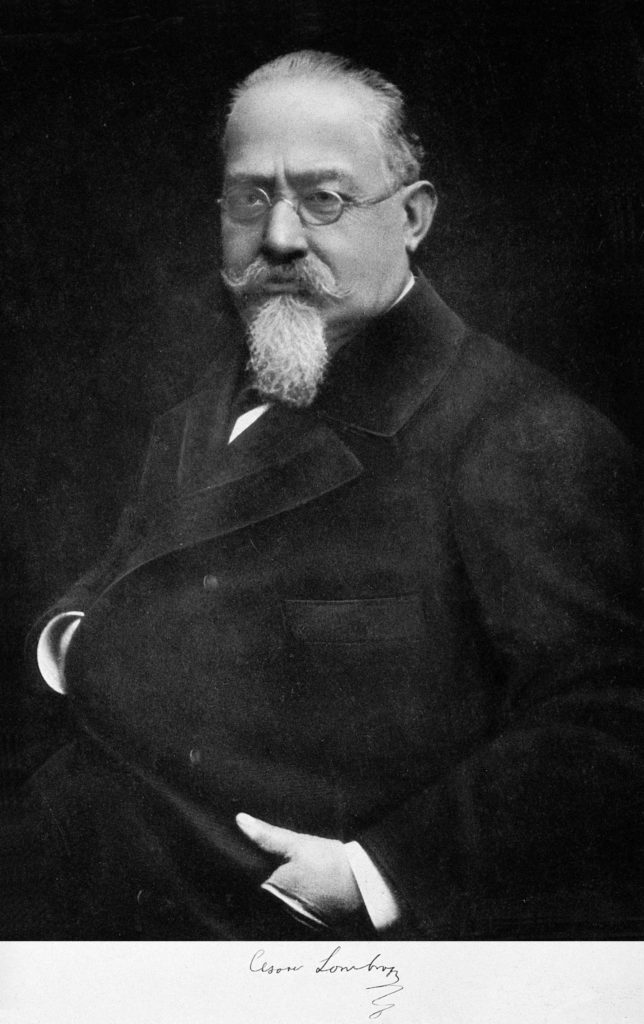

Cesare Lombroso. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Preventing an outbreak…

One of the proponents of the immune system remedy was criminologist Césare Lombroso. In his Gli Anarchici (1895), Lombroso argued for rehabilitating anarchist fanatics through non-violent punishment rather than draconian laws. Repressive state measures, he explained, would merely ‘infect’ new terrorists, just like cholera infected new victims. Lethal punishment only produced martyrs, Lombroso concluded. He figured that terrorism could be cured by addressing its root causes: “Just like we see Cholera strike in the poorest and most filthy areas of the city, anarchy rages particularly in poorly governed places.” Lombroso thus aimed to increase the immune system of a whole society, making its inhabitants less vulnerable to the ‘anarchist-Cholera’. That the statutes of the world’s first international conference against terrorism (Rome 1898) were based on the adopted rules of earlier international conferences on contagious diseases therefore might not be a coincidence.

…or removing bad cells?

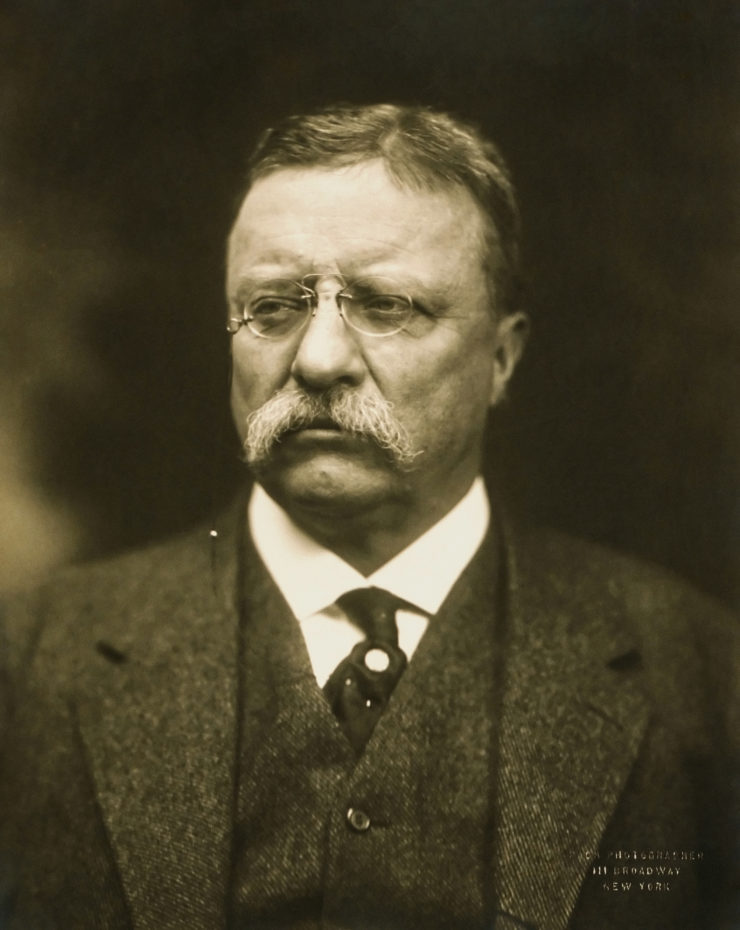

Another nineteenth-century remedy against the ‘anarchist disease’ consisted of preventing infectious ‘cells’ from entering society and cutting out those that had done so already. US politicians and newspapers suggested this kind of treatment after an American-born anarchist murdered President William McKinley in 1901. They presented anarchism as an external infection, introduced by (European) immigrants. More specifically, an article in the New York Times described how anarchism spread like a tuberculosis that infected healthy Americans, and turned them into assassins. Theodore Roosevelt, who succeeded McKinley, declared in his first congressional address in December 1901 that such an external threat could, and should, be surgically removed like a disease. Subsequently, the Immigration Act passed US Congress on 3 March 1903, which prohibited foreign anarchists from entering the United States or allowed for their deportation within three years upon arrival. In practice, however, it proved impossible to diagnose who carried the anarchist disease and who did not. There were no visible symptoms. By 1910, of the millions of immigrants entering the United States, only ten anarchists had been debarred or deported.

Theodore Roosevelt. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Improvement of resilience

The nineteenth-century analogy between terrorism and contagious disease thus resulted in two distinct approaches: one preventive, the other repressive. While Lombroso suggested to ‘cure anarchism’ through the improvement of the state’s resilience, the American remedy merely focused on fighting the symptoms. In Italy, the preventive approach showed immediate results after 1901. As the progressive liberals under Giovanni Giolitti came to power, the Italian government attempted to end violent confrontations with leftist radicals. The government switched from a draconian approach to more constructive prevention: socialists and other leftists were invited to join the cabinet, labour organizations encouraged, strikes no longer prohibited, and freedom of press and association upheld as necessary security regulations for social and political opposition. Giolitti argued that harsh, widely publicized repression only created anarchist martyrs, whereas denying anarchism any form of public attention prevented its growth. He improved the quality of domestic security services and the gathering of intelligence abroad, while ‘heavy-handed police actions carried out in the glare of the media’ were henceforth avoided. Studies into the results of Giolitti’s preventive turn have shown that ‘avoiding such methods in Italy after 1900 rendered the chronic terrorism of the 1890s a thing of the past’.

Dangers of the analogy

Regardless of the metaphors involved, tackling terrorism at its roots, alongside improvement of the state’s (and society’s) immune system, has developed into a standing practice. Comparable approaches to improving societal resilience through preventive measures are still applied today, and, for some present day researchers, epidemiological knowledge might even contribute to determining which factors contribute to receptiveness to radical thought or which social areas are more vulnerable. However, applying the disease metaphor to justify repressive laws against specific individuals or to restrict specific forms of migration did not only prove unsuccessful in the past, it has also been shown to entail great dangers. It is only a small step from selecting ‘contagious cells’ to conceiving of dehumanizing remedies against social degeneration. Just like the American discourse on anarchism, Nazi propaganda singled out its adversaries as a ‘parasitic’ or ‘alien’ biological threat. The analogy between terrorism and contagious diseases emerged in the scientific context of the late nineteenth century, when it could perhaps not yet be envisioned to what horrific ends the operationalization of the metaphor would lead.