USHS Blog

Informal European Security. On the Long Tradition of Interpersonal Police Networks

Today, it may seem as if society is endangered by an ever-expanding concatenation of threats. New media have created digital echo chambers, where fears of global terrorist violence and anxieties over globalization and moral declines reverberate up to the point of cacophony. We are inclined to think such a compression of time and space through modern techniques of news transmission make the times in which we live unique. In terms of security policy and counter-terrorism, the twenty-first century may seem to pose unprecedented problems of interconnectedness, but the solution to those problems may very well be drawn from much older types of security networks. This is illustrated in a recent report on the ‘current policy architecture of the EU in combatting terrorism’ by the European Parliament. The report points to the importance of informal cooperation, at the rank-and-file level of the different national services. In this blog, I refer back to historical instances of this cooperation, not just to provide context, but most of all in order to weigh the validity of the report’s recommendations.

Formal and informal cooperation

The report distinguishes two forms of counter terrorism cooperation. Besides a formal (governmental) channel of cooperation, the authors also identify an informal (professional) channel. They highly recommend that second type of cooperation, calling it ‘extremely important’ and arguing that it ‘should be strengthened, rather than creating yet another framework for cooperation or data sharing’. The suggestion is intriguing. Institutionalized exchanges of information are normally limited to signalling phenomena and sharing analyses, instead of sharing operational records.

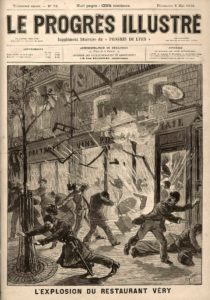

Image 1. An anarchist attack on Paris’ restaurant Véry at the Age of Modern Terror. Source: Wikimedia Commons

European treaties emphasize national sovereignty in the fields of security, policing and justice. Formal cooperation, in other words, is bound to national interest – and the report warns against such restraints. An evaluation of Europol’s activities underlines the importance of communication in (bilateral) ways ‘which are not formally part of Europol’s mandate’. According to the report, informal cooperation in Europe began with the intergovernmental TREVI network (1975-1992). It was, however, the European struggle against violent anarchism of about 120 years ago, a period dubbed the ‘Age of Modern Terror’, that marked the beginnings of informal cooperation and provides us with examples of its benefits.

Facing the age of modern terror

In August 1896, Robert Anderson, the Head of London’s Criminal Identification department, was informed that two Irish-American ‘Fenian’ terrorists had left New York City for Europe. Soon after arriving on the continent, in Antwerp, the Fenians began planning dynamite attacks on the British mainland, to further the cause of Irish Home Rule. Rather than intervening at once, Anderson decided to strengthen his case and let the plot mature. The conspirators were allowed to produce their dynamite and subsequently dispersed across Europe to Glasgow, Rotterdam and Boulogne, from where they supposedly maintained ties with London and Paris as well.

Their spread over Europe confronted Anderson with the problem of national protectionism. Attempts to foster official international collaboration against terrorism had failed time and again by 1896, primarily since more liberal states did not want to give up national sovereignty while handing autocracies tools for general repression of political opposition. As a result, there was no shared legislation on extradition and even the application of uniform police technologies for identification and registration proved to be most difficult. Instead, in an attempt to accomplish some forms of counter approach, Europe’s principal police authorities were granted a certain amount of autonomy by their respective governments, to communicate with one another directly.

Professionals over governments

This development emphasized the discrepancy between formal and informal cooperation. Anderson personally telegraphed his colleagues in Glasgow, Rotterdam and Boulogne on Sunday the 13th of September, after which arrests were made without difficulties. Over the following months, police inspectors from Antwerp and Rotterdam frequented London to discuss the evidence retrieved from their detainees. However, concerted efforts remained limited to a professional level. The success of the informal cooperation nevertheless turned into a failure. None of the national governments was willing or able to extradite the plotters or share the evidence. From France and the Netherlands, the conspirators were even allowed to return to New York.

The episode indicated that cooperation could only take place informally. During the 1890s, policemen from across the continent were allowed to come in touch and formed an interpersonal network of Europe’s most distinguished officials. An epistemic police community developed, allowing police experts to recognize each other and share expertise, technologies and best practices. For instance, Dutch policemen involved in Anderson’s episode returned to London the following year, to study its exquisite detective and identification services, and motivated colleagues from cities like Berlin, to tag along.

Image 2. The interior of Rome’s Palazzo Corsini alla Lungara, site of the international anti-anarchist conference of 1898. Source: Wikimedia Commons

An international anti-anarchist conference in Rome in 1898, involving police officials and diplomats, discussed the question of efficient cooperation at different levels. During this conference, police officials from the Great Powers and their most important partners were able to organise their own, sometimes secretive sessions to discuss their best practices. In particular, the policemen made their diplomats agree on a more standardized and centralized exchange of relevant intelligence, including the joint introduction of uniform technologies. The diplomats in Rome even pondered the creation of a sort of European cooperation through solid formal bonds of shared legislation and extradition treaties, but, in the end, those boundless utopias once again shattered along the lines of national divisions. The professionalization of direct police practices turned out to be the only practical result of the conference; professional security actors further operationalized their existing relations and the interpersonal exchange of intelligence.

Stimulating interpersonal networks

Though innovative steps have been made in European counter terrorism cooperation – including the creation of a European framework for specialized legislation (2002, replaced in 2017), a European CT strategy (2005) and a shared ‘agenda of security’ (2015) – the general lines of the late nineteenth century could be extended until today. The comparison may be a blunt one, but today, like at the 1898 Rome conference, the choice is between the politically utopian creation of a supranational, European FBI that combines all national databases and ends national fragmentation, and the continued strengthening of informal networks for cooperation. The latter is to improve existing coordination between Europe’s separate internal security domains by providing an environment in which professional actors, the EU report argues, ‘will develop an automatic reflex to share relevant information with colleagues in other Member States’. Given historical experiences, we might wonder if it’s time to leave aside the idea of supranational organization with all its national restrictions, in favour of giving back autonomy to professional experts?