USHS Blog

Historicising the Present: Syria through the Looking Glass

Late 2016 was an agonising time for humanity. It beheld the assault on Aleppo; the bombing of schools, hospitals and other civilian targets. We watched videos posted by people from Eastern Aleppo, seemingly trapped in town on 12 December, calling for help in complete uncertainty of what the future would bring. We later read that while tens of thousands of civilians were evacuated by the UN, evacuation buses were shot and people were killed or disappeared at checkpoints. Some of us poured into the streets to protest the bombardments, which indeed worked in the short-run. Some went for the easy way, interpreting all this human misery as their (the Middle East’s) chronic problems. And some of us, including myself, couldn’t help wondering, amidst this emotional intensity, how our stories will be told, when people will look back, say, several decades from now. It left me pondering how we will historicise our sorrowful present, and wherein this sad story we would be.

‘Is it too soon?’

Coincidently I came across a post by Steve Tamari of Southern Illinois University Edwardsville at a history discussion group at about the same time. He was asking whether it was too soon for historians to weigh in on the causes of the Syrian Civil War, or whether we had to wait for it to be over to reflect on its deeper roots. I personally believe that it is never too early to start such endeavours, but what we are to grapple with, I must add, is actually much more complex than we may think. It is a question beyond writing history. This I say, first of all, in reference to my own experience in penning a book on the history of the 1860 Syrian civil war.

Damascus, 1860. Source: WikiMedia Commons

It is difficult not to detect the stark similarities (and obvious differences) between the current war and the 1860 civil strife in which about twenty thousand people died and more than a hundred thousand people became refugees. To mention a few resemblances, both in 1860 and today, the wars resulted from societal polarisation, from tensions between the multiple and intersecting identities of the Syrians – they were not merely born from sectarian or ideological divides. In both conflicts, global imperial actors fanned on causal dynamics as they sought to sustain or establish spheres of influence in the region. In both cases, the local was globalised and the global was localised. In both 1860 and the 2010s, local actors and proxies were initially the major actors of the conflict, and imperial actors intervened in the conflict directly only eventually. Both saw persistent media wars and discursive manoeuvrings.

Consider the heated debate between the US and Russian ambassadors at the emergency session of the United Nations Security Council on 13 December. Samantha Power and the late Vitaly Churkin were accusing each other of being responsible for the atrocities. Power would claim: ‘[Russian] forces and proxies are carrying out these crimes, your barrel bombs and mortars and airstrikes have allowed the militia to encircle tens of thousands of civilians. Churkin would in turn say that Power ‘gave her speech as if she was Mother Teresa herself… I do not want to remind about the role that [the US, France and the UK] played in inciting the Syrian crisis.’ In 1860, the French Foreign Minister Antoine Edouard Thouvenel would likewise accuse the British Prime Minister Viscount Palmerston of being responsible for the probable continuation of massacres in Syria. He would thus justify dispatching French expeditionary troops to intervene in the war.

I believe the greatest similarity between the two wars is that they both have multiple and complex roots which can hardly be explained with a linear narrative. One has to consider, at one and the same time, the geostrategic macro considerations of global imperial powers and local power holders. That is, one has to grasp how their frequently predatory attitudes have threatened the immediate interests of the local Syrians and informed diverse responses from them. Moreover, we have to understand the processes wherein the underprivileged groups were forcibly included or altogether excluded from the global capitalist and regional political transitions.

History in the Making

In bringing to the fore the global-local linkages, I find Tamari’s questions timely and important. Existing studies on the current war hardly cover its complexity. Though some of them, especially Reese Erlich’s Inside Syria, are excellent journalistic works drawing mainly upon interviews with different actors over decades.

Historically speaking, to connect all the dots right now and have a fuller picture of the origins of the contemporary Syrian civil war, we will need studies with multifocal lenses. It will demand holistic approaches that consider the broader international and global systems of rule and control, yet also include the agency and subjectivity of the locales. It will require not only interviews with actors of the war, but also study of the materials that are now being produced by imperial agents such as diplomats, military officers, secret agents and the media, as well as by reactionary actors.

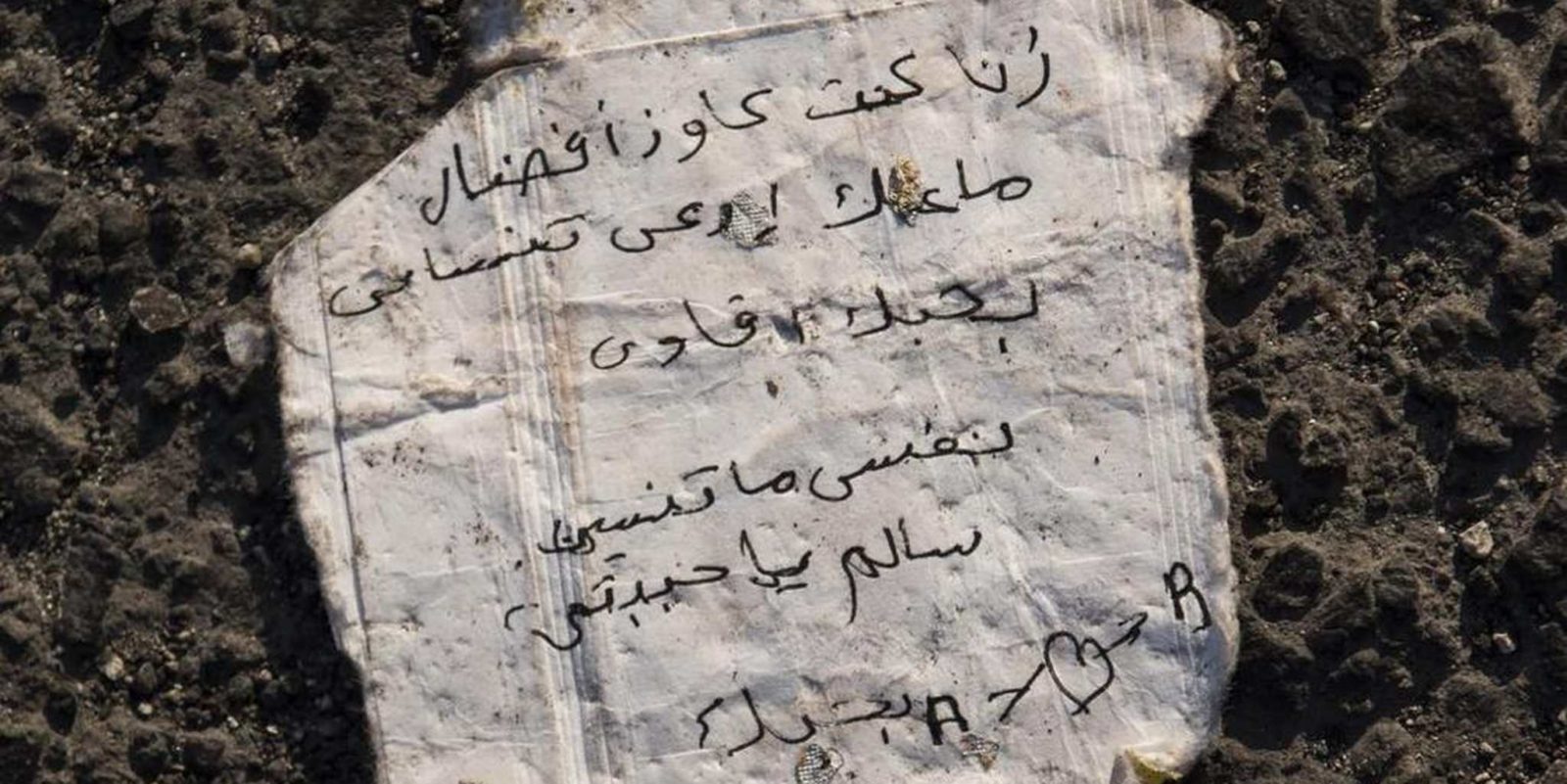

The endeavour to explain will necessitate finding those e-mails and messages deleted and thrown into the wells of cyber infinity; or perhaps reading those slightly torn letters penned from the refugee camps in Europe, Lebanon and Turkey by those now unwanted in their new environments. It will call for exploring the diaries kept by actors of the war to trace what drove them to be part of the conflicts in the first place. And it will beg historicising our intersubjective insecurities globally, without sticking to the perspectives of the last fifteen years or the powerful only.

We do need to start historicising the present now, because now is the time to start raising our voice with an inclusive tone. We have to write because it shall be recorded in history, it shall be remembered which of us remain with humanity, not in our comfort zones; which of us bury our heads into the convenient sands of our immediate lives; and which of us side with those politicians, far-right or not, who capitalise on human miseries, who aim to build physical and mental walls, categorising and polarising us, perpetuating a colonial tradition in a new setting. We have to act, because history is not only about big moments, it is an everyday struggle; and the act of historicising is not only about writing history, but also representing it in action. Wherein this sad story we will be, that’s entirely in our hands.