USHS Blog

What happened to Mr Cutsi? The Curious ‘Murder’ of the Dutch Consul in Damascus

“Kill them!”, “butcher them!”, “plunder!”, “burn!”, “leave not one!”, “not a house, not anything!”, “fear not the soldiers, fear nothing!”… Dreadful as they were, these were the cries that roared in the streets of the Christian quarter of Damascus that afternoon. It was the ninth of July 1860. The civil war in Mount Lebanon that had begun in late spring, now spilt over into the inner regions of Ottoman Syria. Within two days, Damascus had turned into hell on earth. Around three thousand Christians were murdered by a poverty-stricken Muslim mob, their houses and shops pillaged, and tens of thousands became refugees, rushing to the coasts of Lebanon to survive. Amidst all this terror, a story of murder and ‘humanitarian’ intervention, of national dignity and human touch unfolded—a curious story that has long been forgotten and that two students at Utrecht University have recently re-visited.

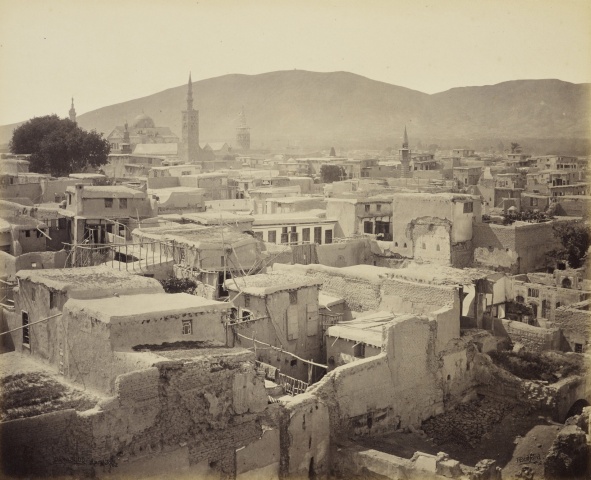

Damascus – Christian Quarter, 1860. Source: royalcollection.co.uk

‘The Foreigners’

Western consuls and their premises were a main target of violence and plunder in Damascus. Impoverished artisans and tradesmen saw them as symbols of decades-long foreign encroachments, as reasons for their increasing destitution and as a disruptor of the community’s moral values. When the mayhem began, the Western agents left aside all their quotidian rivalries, firmly stuck to each other and sought shelter in the houses of the Muslim notables in town, such as the Algerian resistance leader Abd al-Qader or Muhammad al-Sawtari, the nephew of a senior Ottoman officer. The thing was: nobody had news on S.A. Cutsi, the consul of Kingdom of the Netherlands. He had vanished without a trace since the outbreak of the events.

The day Mr. Cutsi disappeared, the American vice-consul Mikhayl Mishaqa could only just escape a horrendous end at the hands of the mob. Mishaqa was cornered by attackers waving axes and swords. He could run away only by distracting them, throwing the coins in his pockets and exploiting that obnoxious moment of oscillation between bread and hatred. Mishaqa’s frightful experience was taken by his colleagues as an omen of Cutsi’s poor fortune. Three days later they were convinced that he was dead.

Jean-Baptiste Huysmans’ illustration of Abd-al Qader as the saviour of Christians in Damascus. Source: Wikipedia.com

Murder and Diplomacy

Before the news of Damascene massacres arrived, a diplomatic deadlock had formed with regard to the French plan of dispatching troops to intervene in the war. The plan was endorsed by most other Great Powers, but Britain and the Ottoman Empire were reluctant. They suspected that Napoleon III had ulterior motives with this intervention. Radical intellectuals such as Karl Marx were writing that the civil war in Ottoman Syria (and the concurrent uprisings in the Ottoman Balkans) were nothing but products of French and Russian machinations, aimed at ending and replacing the dominant control of Britain over the Ottoman empire.

When the consuls’ dispatches arrived in their capitals one week after the atrocities, the deadlock was broken. Papers soon picked up on the news, exaggerated the details of the massacre and heightened public outrage over Christian losses. Faced with news that the premises of the Western consulates were plundered and the Dutch consul was murdered, the British cabinet gave in. In early August French forces left for Syria. This was how the first ‘humanitarian’ intervention in what we today call the Middle East came into play.

Solving the Cutsi Case

The intervention has inspired a huge body of scholarly work, but it has never been explained how Mr. Cutsi was murdered, how the Dutch government reacted to it and what happened in the murder case.

A Refugee Camp in Syria in 1860. Source: Wikipedia.com

Last October, in a module I teach at Utrecht University, I assigned some of my students the task of solving the mystery around Cutsi’s murder. Two of them, Bert-Jan van Slooten and Anouck Mes, went through 19th-century Dutch newspapers and parliamentary proceedings. They became the first to uncover how several papers reported on the murder with dismay and how the Conservative deputy R.J. Schimmelpenninck brought these reports to the attention of the parliament. The Foreign Minister Jules van Zuylen van Nyevelt promised to preserve the Dutch national dignity by pressuring the Ottoman government to pay a compensation and by dispatching three warships to Syria to protect Dutch subjects. Bert-Jan and Anouck also found out why the issue of the murder immediately dropped from the agenda after July 1860: Cutsi was alive.

The Lines in the Sand

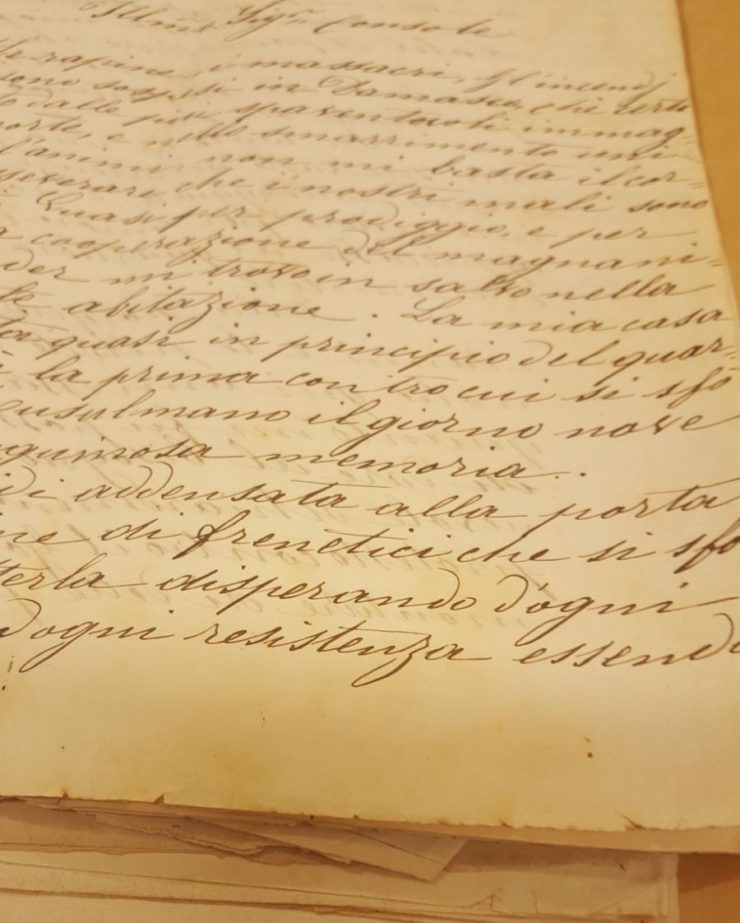

My subsequent visit to the National Archives in The Hague confirmed my students’ findings. The archival sources disclose that on 20 July 1860, Cutsi, after days of silence, re-appeared with a letter addressed to W.E. Frecken, the Dutch Consul in Beirut. He explained that, when the massacres began and his house was besieged, he and his son sought shelter in the house of their Muslim neighbour, Hussein Agha, who accepted them at the risk of his own life. The two then hid in the chimney of Hussein’s house for thirty-six hours. After the angry mob dissolved, they disguised themselves as Bedouins and found refuge in the mansion of Abd al-Qader, along with the other Western consuls.

Cutsi’s letter dated 20 July 1860. Source: The National Archives, The Hague

The false news of Cutsi’s death – to a certain extent – played a crucial role in the 1860 ‘humanitarian’ intervention in the Middle East. The ‘murder’ underpinned imperial allegations and was used to legitimise the intervention. Once we unearth the true story, however, we see a different picture altogether. We encounter a situation where prejudices were overcome, and Syrian inhabitants were willing and able to rescue the Dutch consul and his family. Sadly, rumours about this fortunate outcome did not spread as wide as the hysteria regarding ‘Muslim’ bloodshed. Yet mutual aid worked, both back then when lives were saved regardless of identities, those lines in the sand, and now, when my students solved the Cutsi case.