USHS Blog

Fishing in Troubled Waters

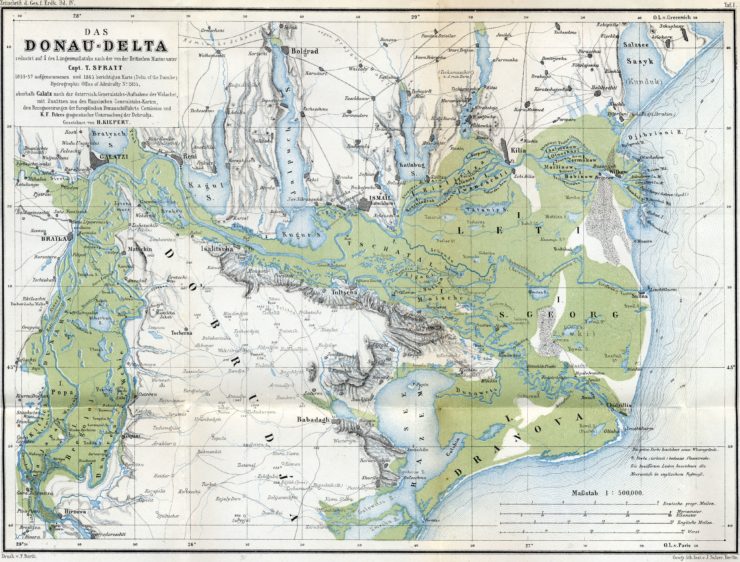

The Danube Delta, a UNESCO World Heritage Site since the early 1990s, is the ‘largest and best preserved of Europe’s deltas’, the home of ‘over 300 species of birds as well as 45 freshwater fish species in its numerous lakes and marshes’. Today, it is aggressively advertised as ‘a wildlife enthusiast’s (especially a bird watcher’s) paradise’. It may be full of picturesque sceneries, but the delta is no Eden for the local communities, who live isolated among a labyrinth of canals, marshes, and reed islands, intersected by the borderline between Romania and Ukraine. Some of these remote habitations are still home to a group which has lived there for centuries: the Lipovans or Old Believers. The Lipovan communities, dependent as they are on fishery, have seen many years of hardship – now as much as ever before. Their situation reflects the human insecurities plaguing communities that are dependent on natural produce. By looking at the enduring plight of this group living in a border zone we get a clearer sense of how geopolitical struggles and environmental challenges lay at the base of the same human security concerns.

Border changes and political insecurity in an inter-imperial periphery

The Lipovans migrated westwards during the eighteenth century, fleeing religious persecution by Russian authorities. One of the places where this Slavic population settled was the Danube Delta, on the fluid and winding border between Moldavia and its suzerain power, the Ottoman Empire. When Tsarist Russia annexed the eastern half of Moldavia in 1812 and took over the entire delta in 1829, this border zone became the meeting place of two rival empires. As trade and navigation along the Lower Danube developed later in the century, Austria, Britain and France also increased their economic activity in the area.

The Lipovans were thus caught up in the vortex of European power politics, even if they lived secluded lives in traditional ways. In fact, borders changed in the delta after every major European crisis (in 1812, 1829, 1856, 1878, 1918, 1940, 1944, 1991). The fate of the Lipovan community of Vylkove (Vâlcov), the main hub of the Lower Danubian fishing industry, is illustrative of the human and economic insecurities generated by such border instability.

Communal and economic insecurities

The stipulations of the Paris Peace Treaty of 1856, for instance, created many local difficulties. The burgh of Vylkove became part of Moldavia, while the fishing grounds were given to the Ottoman Empire. Locals bared the brunt of these decisions through deteriorating material conditions. The Lipovans fished in Ottoman waters, and had to pay large tithes and export duties to the Ottoman authorities. When they brought their catch home, they paid import duties too. Their main outlets remained in the Russian Empire, so they further paid customs tolls to export the goods across the Moldavian border. The Lipovans also lost significant economic privileges, such as the right to cut firewood and to harvest reeds in the delta. These advantages were forbidden or heavily taxed by the Ottomans, adding to the economic burden of the community.

National interests and state security

All in all, the Lipovans’ situation had become so miserable that the communal leaders considered migrating while the fishermen kept complaining to the Moldavian and Ottoman authorities for redress. By the late 1850s, the Moldavians found their lament useful for an exercise in nation and state building. Relations between Moldavia and the Porte had worsened, and hospodar Alexandru Ioan Cuza used the Lipovans’ case to both expose the Ottomans’ abuse and to strengthen the country’s international status. He relied on his French connections to impose the question on the agenda of the 1856 Paris Treaty signatories, his country’s protectors. At the same time, the fishermen’s plight was internationalized by Russia, which acted as defender of its former citizens’ rights and implicitly condemned the unjust territorial loss it had suffered in 1856. Through an ambassadorial decision taken in Istanbul by the representatives of the Concert of Powers, the European Commission of the Danube was requested to resolve the dispute.

An international arbitration

The European Commission had been charged with a technical task (i.e. to remove the obstructions that hindered navigation along the Lower Danube), but it also started to act as a source of law and order in the Danube Delta. It was a territory where Ottoman and Moldovan state authorities were rather weak, making it a haven of adventurers, deserters, and criminals. Using its own officials and backed by naval forces stationed in the area, the Commission acted to also provide for the human security that lacked in this inter-imperial border zone.

In June 1861, after half a year of complex deliberations on border issues and the local community’s fiscal plight, the Commissioners created a more convenient borderline. Additionally, the Moldavian and Ottoman authorities were urged to conclude a joint agreement to protect the fishermen’s former privileges by granting them customs and tithe exemptions. The alleviation of human insecurity, however, proved short-lived. In 1878 the locals’ fate changed once again, as Russia re-annexed southern Bessarabia, and the delta was transferred from the Ottoman Empire to independent Romania, with new instability in administrative or fiscal procedures.

New economic and environmental threats

During the 150 years that have passed, borders have continued to be repositioned while everyday fishing practices were deeply affected by the coming of the modern world. The hydrotechnical works of the Danube Commission in the late nineteenth century brought insecurities of a new kind and scope. The works diminished fishing grounds. Later projects of diking and land reclamation – like the communist regime’s plan to turn the delta into a huge agro-industrial zone – only added to the loss. Industrial pollution further impacted the biota. The largest environmental disaster in terms of fishing resources has taken place during the post socialist years, which have so far been marked by insufficient legislation for the protection of endangered species, industrial overexploitation of the economically productive species, defective restocking policies, and endemic corruption of protection agencies.

For the traditional fishermen communities living in the Danube Delta, the inter-imperial political instability of the past centuries (visible in frequent border changes) has been replaced with internally generated environmental threats to their main supply sources. With continuous economic insecurity, deterioration of the natural habitation in the delta and difficult access to public services, all threats considered within the human security paradigm, the Lipovan community feel they are an endangered species.