USHS Blog

Decolonizing the Curriculum

I sat in front of the textbook, staring at the passage on the Industrial Revolution entitled “Why Europe.” It read:

“Centralized state power and highly developed legal systems [in England] protected merchant trade and facilitated the accumulation of wealth for further investment. Such security was non-existent in other parts of the world, such as the Ottoman Empire, where corruption hampered the development of a commercial spirit.” [Noble et al, Western civilization, p. 576.]

Which made me do a double take. I was shocked – not only because it misrepresents history but also because this kind of thoughtless stereotyping has far-reaching implications for social cohesion and, ultimately, security.

The problem explained

Why are these concerns so crucial? For a start, most historians would be frustrated by misrepresentation, simplification, and failure to substantiate facts. In this case, the implication that England was not corrupt, in contrast with the “corruption” in the Ottoman Empire, is false. Just ask the Irish, Scots, or those Indians who were under British rule and engaged in business with the English during the late 1700s-early 1800s. At the same time, as Cemal Kefadar has shown, the myth of Ottoman decline and corruption should be questioned. Here, however, it was reproduced in a textbook, a source that students often read as fact. Perhaps most damaging is the implied opposition between a “highly developed” system in England and the “hampered development” of the Ottoman Empire, a reading that reinforces damaging stereotypes. The idea that a whole population could share in an intangible quality like a “commercial spirit” is dangerous. Generalizations like that take us along the road toward thinking that certain groups of people have innate qualities – for better or worse – and from there it is a short step to “Jewish people are greedy” or “Asiatics are deceitful.” The danger of that thinking for peaceful co-existence and respect for all humans, and thereby for a world committed to respecting human rights, should be obvious.

Noble et al, Western Civilization Beyond Boundaries, p. 577, my annotations.

But isn’t that a lot to take from a single phrase in a textbook? Yes. And no. Actually, it was not the only problematic phrase in this particular textbook: Noble et al, Western Civilization Beyond Boundaries. The textbook also failed to mention the partial contribution of slavery, and the slave trade, to the accumulation of capital that made possible the industrial revolution. And there were other misrepresentations and omissions.

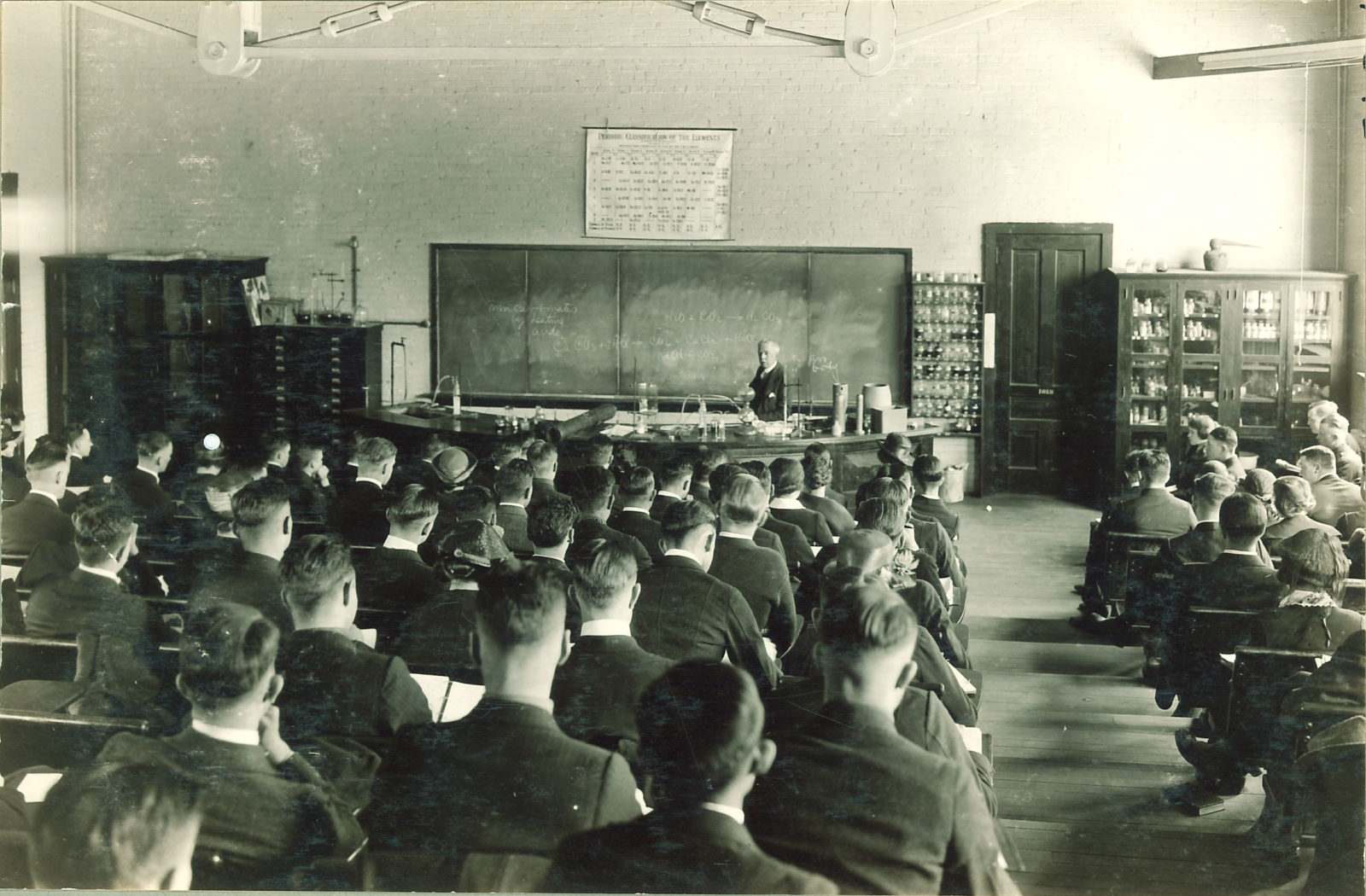

Textbooks are flawed. We all know that. But the way they represent the past has enormous power and so the stakes of choosing them are high. This is one of the major textbooks that first year students in many History programs encounter. They often read it in courses that are titled “Modern History” and “Contemporary History”, but principally deal with European (certainly Western) history.

To me, there is a problem with labelling a course that deals with Europe as a course on the much more universal and global sounding “Modern history.” It makes invisible the contributions of non-Europeans to history. It claims a pre-eminence for European history that ignores and negates the extent of interdependence and interaction around the globe in the past. It carries the risk that students in their first course, in their first year, in their first academic exposure to history, are being given the impression that Europeans have been the most significant force in, or shapers of history. And it happens in hundreds of Universities and Colleges where students might take just one history course in their undergraduate degree. I invite students to question the textbook and discuss who it represents, in order to make the implicit choices in such courses more transparent but that isn’t always the case in big intro-level history courses. This is an ethical problem, it is a historiographic problem, it suggests the legacy of imperialism is still alive and well in many programs. It is a problem for diversity and inclusion. It is also a security problem.

Security and classroom diversity

Misrepresentation is a security problem because when we fail to represent diverse students and their histories in our classrooms and readings, we exclude them. We falsify the past and it has a devastating impact on their present. Students who feel excluded, marginalized, and who are under-represented in the academy often struggle to succeed. UNESCO’s guidelines on inclusion in education illustrate the links between education and peace – “inclusive schools are able to change attitudes toward diversity by educating all children together, and form the basis for a just and non-discriminatory society.” The UNESCO guidelines state that non-discrimination and inclusive education results in greater social stability and peace.

Students who feel misrepresented or stereotyped – in classroom materials, lectures, and textbooks – may distance themselves from the university. Psychologists have shown that feelings of exclusion lead to alienation and aggression. In the context of a classroom, misrepresentation and stereotyping can make success harder. Students who feel excluded can become disaffected with university and drop out – creating and perpetuating further disaffection with the institutions and systems of a society that do not seem to function “for us”, but only “for them.” It can lead to disillusionment with the university and also with the wider systems that have made it so difficult to succeed in the university. Systems in which a student does not see anyone who looks like them teaching, or winning academic recognition, or appearing as leaders in the textbooks they read. Systems (and courses) that do not seem to recognize the achievements of people of their ethnicity, class, or religion and that, therefore, make students feel like success is a battle or they are an outsider. Social psychological research has established that exclusion can lead to aggression, whether on a personal, or group level. Perhaps educators should do more research on how these trends play out in our classrooms.

During class, I spoke to a student who was angered by the quotation about Ottomans that began this blog. Angry students can become disaffected. Misrepresentation and exclusion hurts. Certain groups of students can feel alienated and drop out or continue with a sense of oppression. The resulting absence of diversity impoverishes classroom debate, impoverishes collective and collaborative learning, and perpetuates lines of division that can rend societies apart. Divisions between “us” and “them” impact security and peace. Disaffection can be a fertile ground – in the worst case scenario – for radicalization, although the research on education and terrorism is complicated.

The positive approach

Conversely, classrooms that bring diverse students together can bridge gaps and transform the worldview of students who come from different backgrounds. Students who talk with students of a different faith or religious background, sexuality, or ethnicity, are more likely to understand each other and build inclusivity into their daily lives. Classroom conversations can challenge even the most entrenched extremist worldviews.

This set of classroom dynamics is why my jaw dropped open at the textbook. It is why I believe so strongly in decolonizing the curriculum, in being careful about centring Europe in our teaching, and I advise educators to be transparent when we do. Building open-to-diversity teaching and learning environments is essential. I commit to that from an ethical point of view. As it happens there are security pay-offs too.

One Response to “Decolonizing the Curriculum”