USHS Blog

A Forgotten Hero? Sir Richard Wood’s Most Adventurous Decade in the Levant

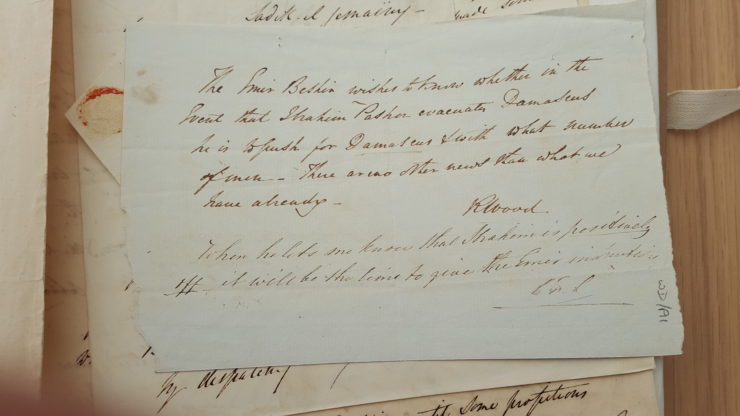

The enduring fame of Thomas E. Lawrence (1888-1935) probably relies mostly on the romantic reconstruction of his life story in the 1963 movie Lawrence of Arabia. Thanks to this film, Lawrence is known today as a British hero who was enormously important in sustaining imperial interests in the Levant during World War I. As a man on the spot, he acted as a connector with local authorities, and helped organise an Arab revolt against Britain’s Ottoman adversaries. The fact is, another man named Sir Richard Wood (1806-1900) had some eight decades earlier undertaken similar missions in the Levant. He too had obtained colossal, if not more significant, political concessions for Britain in an age of global imperial rivalry, and played a decisive role in securing British and Ottoman imperial interests in the region. However, except his private correspondence, nothing has been published about him to this date. Not even on Wikipedia.

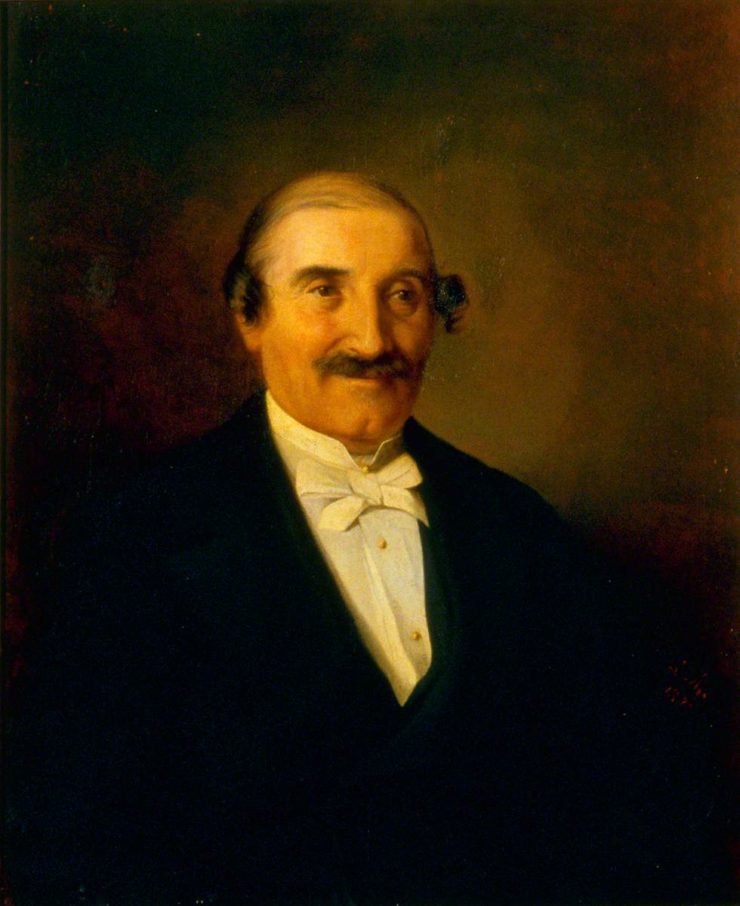

Mayer, Lieron; Sir Richard Wood (1806-1900), Consul-General to Tunisia (1855-1879). Source: Government Art Collection

Between Two Empires

The most adventurous decade of Wood’s life began in 1831. This was the year French-backed Pașa of Egypt Mehmed Ali rose against Sultan Mahmud II and dispatched his son Ibrahim Pașa to invade Syria. Mehmed Ali’s rise in the Levant was a threat to the British Empire, not only because France could now exercise immense influence over the routes to India, but also because the territorial integrity and existence of the Ottoman Empire was put in jeopardy. Europe’s balance of power, peace and security were thought to depend on that integrity. Wood found himself tasked with a mission to secure British interests in Syria at this critical juncture.

The son of a dragoman in the British service, Wood was born in 1806 and grew up partly in the imperial capital of the Ottoman Empire and partly in Exeter, where he went to a boarding school until 1823. He eventually became a dragoman himself, being fluent in Turkish, Greek, French and Italian. Moreover, he was well versed with the specificities of the Ottoman world and local ways of doing politics. This in-betweenness endowed him with a unique position and life-story.

The Missions in the Levant

His versatile skills and knowledge got Wood dispatched to Syria in 1831. According to the American vice-consul of Damascus Mikhayl Mishaqa, Wood came to the region ostensibly to learn Arabic. But his undercover purpose was to find means to undermine Ibrahim Pașa’s government in the Levant. Soon after his arrival, he went to observe Ibrahim’s siege of Acre – the very castle that Bonaparte had failed to conquer in 1799. He wrote to Istanbul that he mistook Ibrahim to be a cook at first sight. In 1834, as Egypt officially established its authority in the region, Wood returned to Istanbul. There, he had long talks with the British ambassador Lord Ponsonby, concerning plans on how to oust Ibrahim from Syria and undermine the increasing Russian influence over Istanbul, which came with the rise of Egypt.

In August 1835, when Wood set for Syria one more time on the British ship The Mischief, a local Syrian revolt against Ibrahim had already begun due to mass conscription and heavy taxation. Wood attempted to gain the Amir of Mount Lebanon, Bashir Shihab II, to the anti-Egyptian cause, but the effort bore no fruit. He then left for Kurdistan to observe the Ottoman imperial army, which was on a punitive campaign against the Russian-backed Kurdish Mir Muhammad (Rawanduz) Bey. On his way, Wood caught small-pox in Aleppo, typhoid in Mosul, heat-stroke on the Tigris, a lance wound in the knee bestowed by a desert tribesman in Tripoli, and a head injury in Kurdistan after which his eyes and complexion were permanently damaged. At his arrival in Kurdistan, he made a personal interview with Rawanduz, who had never heard of England or the Anglo-Russian rivalry for that matter, but nonetheless could be convinced to come to Istanbul and negotiate his terms with the Sultan.

A Man in the Middle

Wood returned to Syria again in 1840. This time, in a similar vein to Lawrence, he played an active role in the organisation of a revolt by the local Druzes and Maronites against the Pașa of Egypt. With competencies endowed by both British and Ottoman imperial authorities, he was now truly a man in the middle, acting as an agent of both local and imperial interests against Mehmed Ali Pașa. After a joint naval mission of Austria, Britain and Ottoman Empire in September, and the restoration of power back to Istanbul the following month, Wood emerged as one of the most powerful men in Syria, possessing authority to sack or hire local amirs. Thanks largely to his successful mission, Britain came to enjoy, as he writes, “a greater amount of influence … than any other foreign power.” The next year, he was appointed as consul to Damascus, where he would play a decisive mediating role between local and Ottoman authorities during the Maronite-Druze wars in 1842 and 1845. He left the Levant in 1857 to take up a post as consul of Tunis.

Wood’s story clearly has many more fascinating tinges that deserve to be reconstructed in nuanced books. He could even feature easily in an action-packed, yet tastefully dramatic movie. Let’s hope though that if he is ever recognised as a forgotten hero and such a movie is made one day, his story, unlike that of T.E. Lawrence, will not be laden with Orientalist clichés and stereotypes, plainly dividing the world into (Eastern) villains and (Western) heroes. Having spent a life transcending irksome cultural patterns, he was no man to simply see the world in such a clear-cut binary fashion, nor would he probably want us to see his life as such.