USHS Blog

The State of Emergency, Part 1: Historical Trajectories

Fears of terrorism are often exploited to bend the rules of government. Only last year, following the stabbing rampage by three men at London Bridge and Borough Market that killed eight people and injured over forty others, UK Prime Minister Theresa May called to restrict human rights in favour of counterterrorist jurisdiction. She declared to be willing to ‘restrict the freedom and movements of terrorist suspects when we have enough evidence to know they are a threat, but not enough evidence to prosecute them in full in court. And if our human rights laws get in the way of doing it, we will change the law so we can do it’. On several occasions, May backed a (temporary) departure from the European Convention for Human Rights (ECHR), which Britain has abided since 1953. British politics are not unique. In July 2017, the German state of Bavaria adopted a new law extending the possibility to detain terrorist suspects without a formal charge. The United States and France already applied special emergency legislation years ago.

This blog is the first part of a diptych, in which we focus on the practical implementation of the state of emergency and the (potential) dangers entailed by it. In the face of disasters, civil unrest or armed conflicts governments possess a broad span of responses. This includes new legislation, emergency measures or, as ultimum remedium, a full state of emergency. It is generally understood that such a binary state of emergency allows a government to take extraordinary actions that are normally beyond their powers. ‘Sovereign is he who decides on the exception,’ Carl Schmitt argued, underlining the state of emergency’s strong executive power, unhampered by constraints of legality. The intensity of government responses to terrorism developed throughout history. In response to unprecedented terrorist violence in the 1890s, for instance, new, exceptional legislation was introduced in France. Over time, however, the legislative palette was supplemented by a more powerful executive tool: the ‘state of emergency’ (état d’urgence). In the next blog, we contrast these examples with contemporary state reactions to terrorism and question the effectiveness of the state of emergency against terrorism.

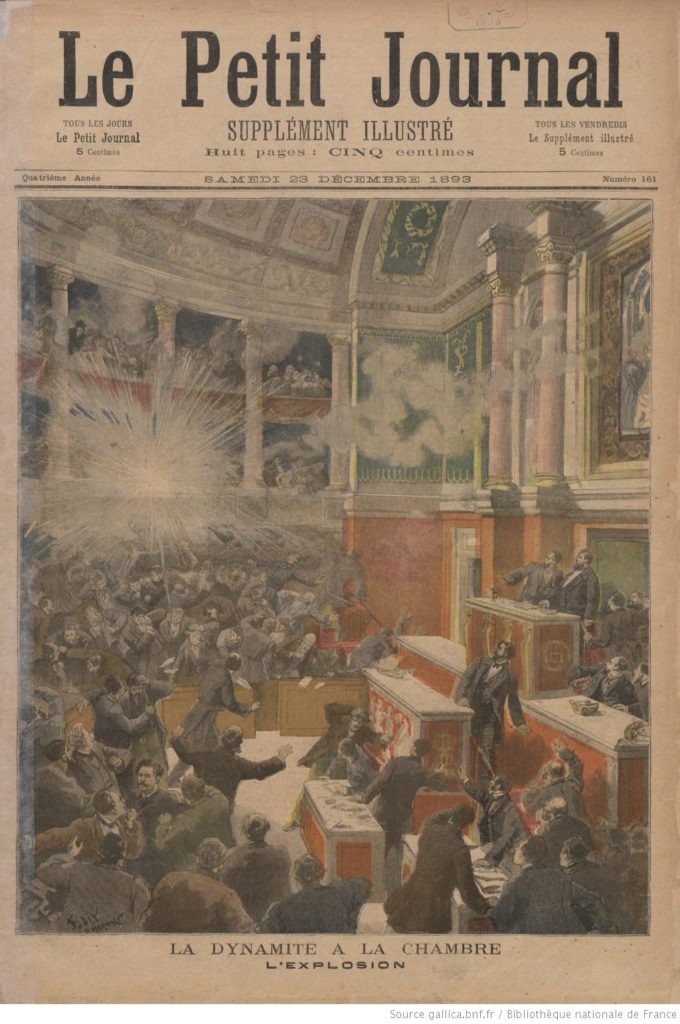

Anarchist dynamite attack in the French Assembly, 1893

‘Villainous’ French laws

On 9 December 1893, the French National Assembly in the Palais de Bourbon, located in the heart of Paris, was startled when the anarchist Auguste Vaillant tossed a small bomb into the meeting, only causing some minor injuries among the assembled representatives. Nevertheless, after years of anarchist violence, the republican government recognized the attack as a window of opportunity to implement long-desired draconian measures to control the whole social movement of anarchism. An existing legal response like the ‘state of siege’ (état de siège), which bore a military character, would be too disproportionate to pass in parliament – it had incidentally been applied during instances of war or internal unrest, such as 1848. Instead, the government scaled up its legislative possibilities within days: on 12 December, the freedom of press was limited and the police was allowed to seize newspapers and make preventive arrests. During a second meeting, less than a week later, the formation of associations with the intent to commit violent acts was sanctioned with harsh penalties.

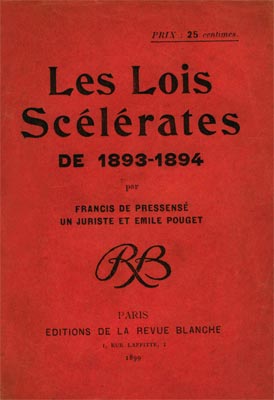

Partly due to the introduction of these laws, French president Sadi Carnot received hundreds of threatening letters until 24 June 1894, when an Italian anarchist murdered him. Again, legislation was stretched even further. Amendments soon restricted, among other things, the possession of anarchist literature and journals. Up to that point, lawmakers operationalized two individual attacks to limit an entire social movement’s freedom of speech and press. Their measures provoked fierce protest from socialist parliamentarians, who feared the legislation would soon be applied against all Leftist opposition. Around the turn of the century, some parliamentarians denounced the laws for being so controversial, they dubbed them les lois scélérates, or ‘villainous laws’. This term is still applied in France today, to designate any harsh or unjust laws: Jean-Luc Mélenchon recently labelled anti-terrorism legislation along these lines, as they could be used for the repression of whole social movements.

Published booklet on the ‘villanous laws’, 1899. Source: WikimediaCommons

Consequences of new emergency laws

Naturally, the controversial character of the new anti-anarchist legislation was reflected in its consequences. Whereas the measures provided policy makers and security services with improved tools in their search for potential evil-doers, the anarchists were criminalized instead. Thousands of households of presumed anarchists were ransacked all over the country, hundreds of persons were arraigned for their alleged involvement in criminal conspiracies (most of them had to be discharged for a lack of evidence) and the number of printed anarchist periodicals dramatically dropped from about 250 in 1892 to less than forty in 1894. Over the course of the following years, anarchists were repeatedly arrested without any hint of evidence, other than their appearance in years-old police files. Many suspect French citizens sought political refuge in places like London.

Although rather far-reaching, the French responses to anarchist terrorism were but one example. Between 1892 and 1896, exceptional repressive legislation was put in practice in at least Denmark, Italy, Portugal, Spain and Switzerland. The character of these laws begs the question of finiteness and accountability: if extraordinary counterterrorist legislation is operationalized, does this come with self-regulating mechanisms, that is, checks and balances?

Toward a state of emergency

The French laws of 1893 and 1894 did not contain mechanisms to assure expiration and checks against excesses. For that reason, even while its application diminished over the years, the anti-anarchist laws remained in effect for about a century, until their official abrogation by President Jacques Chirac in 1992. With their counter anarchist character, the laws could not legislatively contain new threats. In the context of the Algerian War of Independence, a tool called ‘state of emergency’ (L’Etat d’urgence) was introduced on 3 April 1955, granting the government with extraordinary powers during massive violations of public order or public calamities. The next blog shows in more detail how the term ‘emergency’ implies a temporary state during which extraordinary powers are needed, as opposed to a ‘normal state’. As a follow-up, one could wonder what the present-day legacy of these historical emergency measures is. As officials began to use the label of ‘state of emergency’ itself, did they become more cautious and aware of harsh consequences? In the following blog, we answer those questions by comparing nineteenth-century France to today’s states of emergency.